|

Caspar Vopel |

GLOBUS VON VOPELIUS, KÖLNNISCHES STADT-MUSEUM: KSM 1984/447, A Manuscript Celestial Globe, 1532

|

Caspar Vopel

GLOBUS VON VOPELIUS, KÖLNNISCHES STADT-MUSEUM: KSM 1984/447

A Manuscript Celestial Globe, 1532

Dal saggio di EllY Dekker del 2010 riproduco di seguito la descrizione del globo celeste manoscritto del 1532 di Caspar Vopel ora depositato presso il KÖLNNISCHES STADT-MUSEUM con il codice KSM 1984/447

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Vopel%202010%20base.htm

Caspar Vopel (1511–1561) was born in Medebach, a small town not far from

In

1526 he entered the

Vopel became a well-known cartographer and was also active as an instrument

maker: (3)

Although his world map and his maps of Europe and the

This paper aims to fill in the gap by describing Vopel's celestial globes and

maps, with special attention given to innovations introduced on their initations

and derivatives.

In

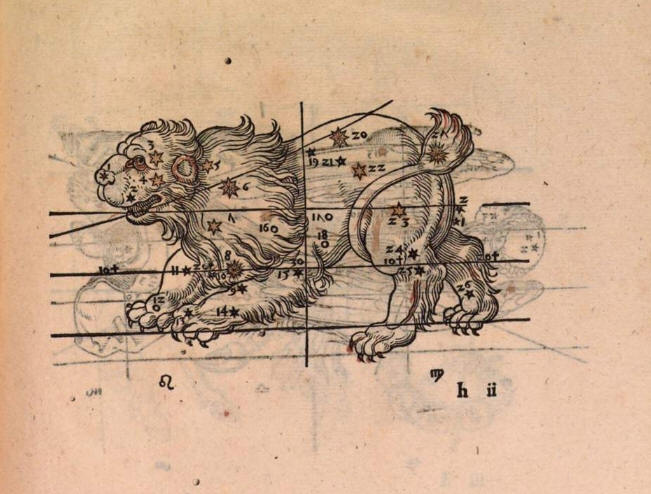

discussing Vopel's celestial cartography I follow existing conventions and

denote constellations by their Latin names. Subgroups, such as the Pleiades, are

referred to by their English names. Stars are identified in one of two ways: by

modern convention or by the serial number from its Ptolemaic constellation. Thus

Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, is denoted as α Leo or Leo 8. Unformed stars

of a constellation, listed by Ptolemy separately after the ‘formed’ stars

because they are located outside the imaginary constellation figure, are

numbered as 1e, 2e and so on, with ‘e’ standing for external. Thus the first of

the unformed stars of Leo is Leo 1e, the second Leo 2e. (5)

The lasting merit of Vopel's printed globe and maps—or so it appears in retrospect—is the images of two star groups, Antinous and the Lock of Hair, better known as Coma Berenices, neither of which had previously been represented graphically. Their introduction on Vopel's printed globe of 1536 started a process by which the two groups came to be recognized as individual constellations. Since then, many other new constellation figures have been added to the celestial sky, sometimes for unformed stars in the northern hemisphere, at other times for stars newly recorded in the southern sky during voyages of exploration. The impact of Vopel's initiative raises a number of questions including why Vopel introduced the images of Antinous and Coma Berenices and what the reaction of his contemporaries was. Before dealing with these questions, however, we need to look at Vopel's various undertakings in celestial cartography.

https://www.kulturelles-erbe-koeln.de/documents/obj/05741337

Vopel's earliest surviving piece of work is his manuscript celestial globe of

1532, now in the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum. (6)

It

has a diameter of some

Like all globes made in the Renaissance, Vopel's presents the 1025 so-called

fixed stars described in the star catalogue in Ptolemy's Syntaxis mathematica,

a second century ad astronomical work devoted to

the motions of the wandering stars, or planets. (8)

The fixed stars, discussed in books VII and VIII, serve in this context as a

reference grid for locating the planets. The star catalogue is organized as

follows:

For each star (taken by constellation), we give, in the first section, its

description as a part of the constellation; in the second section, its position

in longitude, as derived from observation, for the beginning of the reign of

Antoninus…; in the third section we give its distance from the ecliptic in

latitude, to the north or south as the case may be for the particular star; and

in the fourth, the class to which it belongs in magnitude. (9)

The recorded star positions are valid for the epoch 137 ad,

the beginning of the reign of Antoninus. Since precession causes the equinoxes

(the points of intersection between the ecliptic and the equator) to drift

slowly with respect to the stars in the course of time, the stellar longitudes

have to be adapted for later times.

Ptolemy's Syntaxis mathematica was transmitted to the Latin West through

Arabic translations circulating in Muslim Spain. The Latin translation made from

the Arabic around 1175 by Gerard of Cremona became known in the Middle Ages as

the Almagest; it was first printed in 1515. The epoch of the catalogue in

Gerard's translation was ad 137. (10)

The star catalogue in the wording of Gerard's translation could also be found

appended to the Latin version of the Alfonsine Tables, a much-copied work

consisting of tables for calculating the positions of the planets. This

‘Alfonsine catalogue’ is adapted to the epoch 1252 (the beginning of the reign

of King Alfonso X of

The astronomical nomenclature in the Arabic-Latin catalogue version was

understandably permeated with names originating in transliterations from the

Arabic. This Arabic legacy is recognizable in the hand-written notes on Vopel's

manuscript globe. Although many details are hard to read, and a complete

description is still a desideratum, I can quote, as an example, the text

for the constellation

|

The second name given to the constellation, vultur volans, reflects the

indigenous Arabic name used in the 1515 edition of Ptolemy's star catalogue.

(12)

The star name alkaÿr does not occur in that catalogue, however, but stems

from an Arabic-Latin tradition connected with the construction of astrolabes

that goes back to the 980s. (13)

Vopel may have taken this name from the star table in Johannes Stöffler's

influential Elucidatio fabricae ususque astrolabii. (14)

The astrological characteristics of the fixed stars were expressed by means of

the influences thought to be exerted by the planets. Vopel probably obtained his

information from the astrological survey of the fixed stars, Nomina &

qualitates stellarum fixarum secumdum Ptol[lemeum], which was added to the

1524, 1545 and 1553 editions of the Alfonsine Tables. (15)

The names Anhelar and Abrachaleus for the brightest stars of

Gemini (α and β Gem), inscribed on Vopel's manuscript globe, are not mentioned

in the 1515 edition of the star catalogue, but they are found in the

astrological survey in the Alphonsine Tables, and their use here shows

that Vopel knew the Tables.

A

number of names on Vopel's manuscript globe cannot be explained by any source

material from the Arabic-Latin tradition. Take, for example, the name Antinous inscribed

below the head of

Its earliest appearance was in the Latin translation made about 1451, at the

request of Pope Nicholas V, directly from the Greek by the humanist George of

Trezibond, or Trapezuntius (1395–1484). The first printed edition of

Trapezuntius's translation appeared only in

Trapezentius's humanist version of the star catalogue differs from Gerard of

Cremona's Latin translation from the Arabic by the use of what humanists

considered ‘good’ Latin. In the translation by Trapezuntius one searches in vain

for names developed from Arabic transliteration. The name Vultur volans, for

For his figures of the forty-eight constellations Vopel copied the style and

iconography of the pair of maps produced by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Conrad

Heinfogel (1470–1530) and Johann Stabius (d. 1522), and published in 1515. (19)

The iconography of what are usually referred to as Dürer's maps, because it was

he who cut the wood blocks, proved extremely successful throughout the sixteenth

century. It served as the model for the planisphere published by Peter Apian

(1495–1552) in 1536 and reprinted with a different type set in his Astronomicum

Caesarum in 1540. (20)

Planisferi di Conrad Heinfogel (?)

Die Karte des Nördlichen Sternenhimmels, Inv.-Nr. Hz 5576

Die Karte des Südlichen Sternenhimmels, Inv.-Nr. Hz 5577

Petrus Apianus

Astronomicum Caesareum, Ingolstadt 1540

Dürer's figures were also used on the printed celestial globe of 1537 produced

by Gemma Frisius (1508–1555) together with Gaspar van der Heyden (c.1496–after

1549) and Gerard Mercator (1512–1595), and on the manuscript celestial globe

made under the supervision of Johannes Praetorius (1537–1616) in 1566. (21)

Belgian celestial table globe, 1537, by van der Hayden, Frisius and Mercator. Royal Museums Greenwich

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/19822.html

Il globo celeste manoscritto del 1532 di Caspar Vopel è descritto anche nella seguente pagina di Astronomie in Nürnberg:

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=vopel-1532

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=sternkarten

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=nachfolger

CONFRONTA CON

Manoscritto di Vienna (1440 circa)

Planisferi di Conrad Heinfogel (?)

Die Karte des Nördlichen Sternenhimmels, Inv.-Nr. Hz 5576

Die Karte des Südlichen Sternenhimmels, Inv.-Nr. Hz 5577

Petrus Apianus

Astronomicum Caesareum, Ingolstadt 1540

Affreschi di Palazzo Besta a Teglio (1550 circa)

e con i

Confronta con le costellazioni di Rusconi

in

Della architettura di Gio. Antonio Rusconi, con centossanta figure dissegnate dal medesimo, secondo i precetti di Vitruvio, Venezia, 1590

Sopra l'origine delle costellazioni australi leggi il seguente articolo di

Per cortesia di

e di Hans Gaab autore di

esamina nelle seguenti pagine le influenze delle tavole del Dürer sulla produzione cartografica celeste successiva

e le carte che hanno influito sulla sua produzione

Von Dürer beeinflusste Himmelskarten

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=sternkarten

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=nachfolger

Altri lavori di Vopel in Atlascoelestis:

Gaius Iulius Hyginus

C. Ivlii Higini, Avgvsti Liberti, Poeticon Astronomicon : Ad Vetervm exemplarium eorumq[ue] manuscriptorum fidem diligentissime recognitum, & ab innumeris, quibus scatebat, uitiis repurgatum, Coloniae 1534

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Hyginusvopel%201534.htm

SPHAERA / ASTRONOMICA / aeri exarata, sicut / eam olim exhibuit Cas/par Vopelius Cosmogr.

quasi copia di

Caspar Vopel, Caspar. VO / PEL. MEDEBACH / HANC. COSMOGRA: / sphæram faciebat. / Coloniae. UN. 1536

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Anonimo%20vopel%201536%20base.htm

di FELICE STOPPA

AGOSTO 2019