|

Huang Shang, Wang Chih-Yuan |

T'ien wên t'u, La mappa delle stelle di Suchow, Cina 1193-1247

|

Huang Shang

Wang Chih-Yuan

T'ien wên t'u, La mappa delle stelle di Suchow, Cina 1193-1247

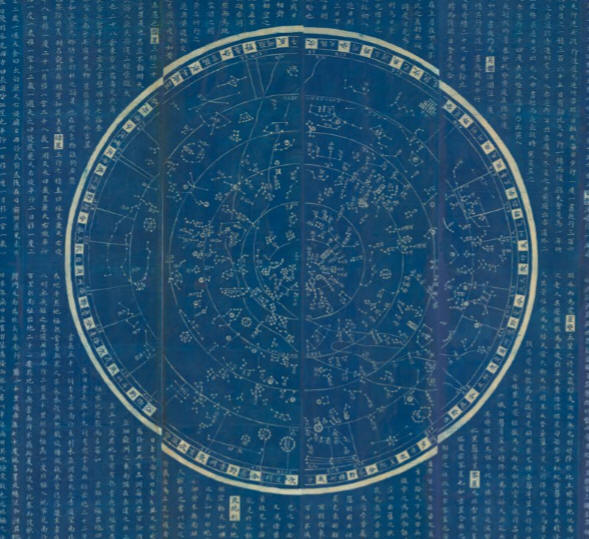

Il planisfero celeste che presento in questa pagina è una rara copia di una stampa per "rabbing" su carta realizzata in Cina tra il 1890 ed il 1910 che riproduce la volta stellata incisa sulla pietra originale nel 1247 da Wang Chih-Yuan ma preparata, compreso il testo esplicativo, dal geografo e tutore imperiale Huang Shang nel 1193.

La tavola su carta, cm 183 per 100, è attualmente messa in vendita da

Paulus Swaen Old Maps che la presenta con una pagina che di seguito riproduco:

https://www.swaen.com/antique-map-of.php?id=27137

Description :

The chart was engraved on stone in 1247 by Wang Zhiyuan, but it is based upon an earlier drawing by Huang Shang, made c. 1190-1193 at the beginning of Shaoxi in the Southern Song Dynasty, while he was entrusted by the emperor as his son's tutor.

The caption at the top consists of three old=style ideographs. Beginning at the

right they are: t'ien, "heaven"; wên "literary" or "scolarly"; and t'u "map",

"chart" or "plan". Herbert A. Giles defies T'ien wên t'u as "A map of the stars".

The stars and lines appear white on a black background. According to Ian Ridpath:

"The planisphere depicts the sky from the north celestial pole to 55 degrees

south. Radiating lines, like irregular spokes, demarcate the 28 xiu (akin to the

Western Zodiac system). These lines extend from the southern horizon (the rim of

the chart) to a circle roughly 35 degrees from the north celestial pole, within

this circle lie the circumpolar constellations, i.e. those that never set as

seen from the latitude of observation.

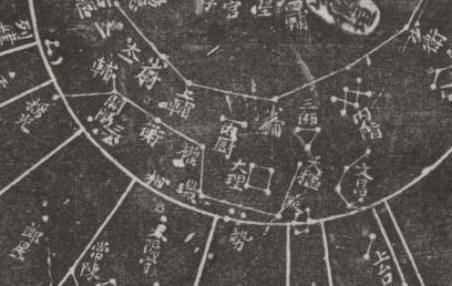

Cerchio delle costellazioni circumpolari a 35° di declinazione. Il luogo di osservazione che genera la mappa è pertanto a 55° di latitudine Nord

Si riconosce il Grande Carro nell'Orsa Maggiore

da Ian Ridpath, Charting the Chinese sky:

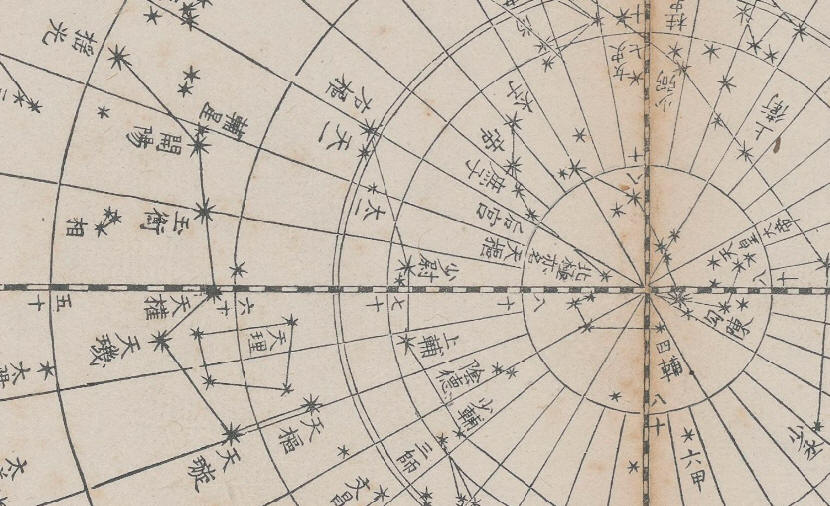

Le 28 mansioni lunari confinate da raggi che

partendo dal cerchio esterno di declinazione posto a - 55° raggiungono

il cerchio delle costellazioni circumpolari

La mansione numero 1, Jiao, le altre si susseguono in senso orario

Eclittica ed equatore si incontrano all'equinozio autunnale e primaverile nei nodi omega e gamma

Two intersecting circles represent the celestial equator and ecliptic, which the

Chinese called the Red Road and the Yellow Road respectively. An irregular band

running across the chart outlines the Milky Way, called the River of heaven –

even the dividing rift through Cygnus can be made out. All 1464 stars from Chen

Zhuo's catalogue are supposedly included (an inscription on the planisphere

tallies the total as 1565, but this is clearly an ancient Chinese typographical

error [and a recent count suggests that the stele depicts a total of 1436 stars]),

not all of the stars show up on the rubbing, however."

The planisphere was reproduced and discussed in a rare book entitled The Soochow

Astronomical Chart, by W. Carl Rufus and Hsing-Chih Tien, University of Michigan

Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, 1945. A copy of this book is in the

Foundation’s library. In 1945, the stela was still located at Suzhou (‘Soochow’

in the old spelling) and had not yet been moved to Purple Mountain. However, the

stela continues to be known as the ‘Suzhou’ planisphere, or astronomical chart.

It was Joseph Needham who classified the chart as a ‘planisphere’, since which

time that term has been adopted for it. Needham used the older spelling of

Suchow, which is however newer than the spelling ‘Soochow’ used by Rufus and

Tien. Suzhou is the modern spelling using the Mainland Chinese Pinyin system of

transliteration.

Rufus and Tien in their 1945 book published an English translation of the full

text inscribed on the stela, together with an extensive astronomical analysis.

Joseph Needham’s discussion of the planisphere is to be found in Volume 3 of

Science and Civilisation in China (Cambridge University Press, 1959), pages

278-9, 281, and 550. The main discussion is found in the Astronomy section of

that volume, and a reproduction of the planisphere itself, but without its

accompanying text, appears as Figure 106 on page 280. (Needham took his

illustration from a reproduction of the illustration appearing in Rufus and

Tien’s book, so it is less clear than theirs.)The text below the chart gives

instruction to the new emperor with information on the birth of the cosmos, the

size and composition of both the heavens and the earth, the poles, the celestial

equator (the Red Road) and the ecliptic (the Yellow Road), the sun, the moon,

and the moon's path (the White Road), the fixed stars, the planets, the Milky

Way (or the River of heaven), the twelve branches, the twelve positions, and the

kingdoms and regions.

The main text on the stela commences in this manner:

‘Before the Great Absolute had unfolded itself the three primal essences,

Heaven, Earth, and Man, were involved within it. This was termed original chaos

because the intermingled essences had not yet separated. When the Great Absolute

unfolded, the light and pure formed Heaven, the heavy and impure formed Earth,

and the mingled pure and impure formed Man. The light and pure constitute

spirit, the heavy and impure constitute body, and the union of body and spirit

constitute man.’

%20copia.jpg)

The lengthy and detailed text preserved on the stela is an extraordinary major

work of Chinese philosophy and early science.

It is difficult to ascribe a precise date to the rubbing, there were periods in

the seventeenth century where rubbing's were popular with the early Jesuits in

the Kangxi court, and again in the eighteenth century in the Kangxi through

early Qianlong courts, but equally in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries during European archaeological explorations of the region.

The last rubbing's were made in the 1990s and the Chinese Government at that

time authorized ten rubbings to be made from the carved stone, nine went to

Chinese museums and institutions, and one is now in The History of Chinese

Science and Culture Foundation.

Whilst several institutions, such as the Suzhou Museum of Inscribed Steles and

the national Library of China in Beijing, and Max Planck Institute for the

History of Science in Berlin hold similar early rubbing's, this particular

rubbing is very rare on the market, currently one other example is for sale with

Daniel Crouch Rare books.

See more about stone rubbing at

www.lib.berkeley.edu/EAL/stone/rubbings.html

Reference : Rufus, W.C. and Hsing-Chih Tien, 'The

Shoochow Astronomical Chart', Ann Arbor, University of

Michigan Press, 1945; Ridpath, Ian, 'Charting the Chinese Sky

(www.ianridpath.com/startales/chinese.htm)'

about

Condition :

Ink rubbing taken from a stele. A rubbing from ca. 1890/1910 of a thirteenth-century astronomical stele from Wen Miao Temple (Confucian Temple of Literati) Suzhou, Kiangsu, China, prepared for the instruction of a future emperor. The stele survives in the Suzhou Museum of Inscribed Steles.

With the usual worm holes, filled in and recently mounted as a hanging scroll

and actually ready to hang.

La Tavola

Note Bibliografiche

Il planisfero di Suchow è stato fatto oggetto di studio nel saggio di W. Carl Rufus e Hsing-Chih Tien, The Soochow Astronomical Chart, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, 1945 che può essere letto alla pagina che indico per cortesia di Hathi Trust Digital Library:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015071688480

Informazioni sul planisfero e sulla rappresentazione del cielo nella cultura antica cinese possono essere lette in questi siti

dedicati alla cartografia celeste:

Ian Ridpath, Charting the Chinese sky

http://www.ianridpath.com/startales/chinese.htm

e

a cura di IDP, International Dunhuang Project

History of Astronomy in China

http://idp.bl.uk/education/astronomy/history.html

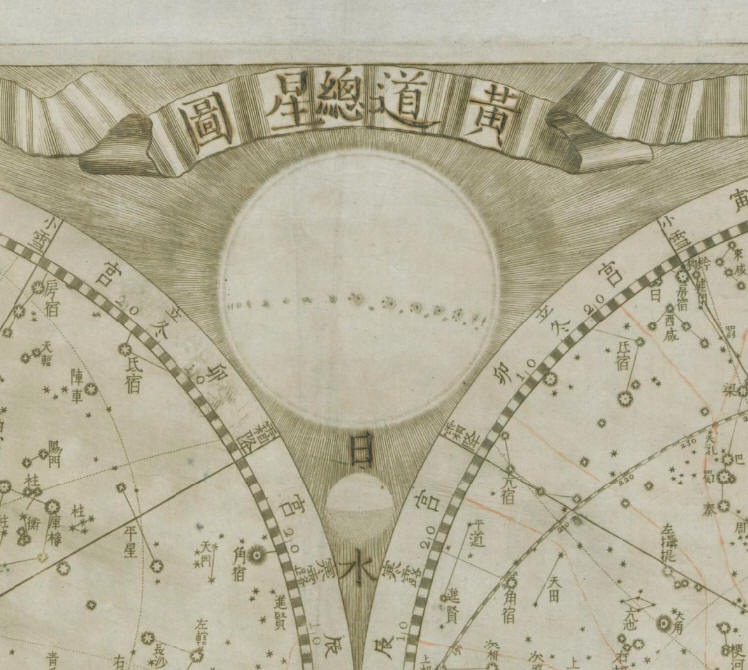

La stessa carta celeste, con pochissime differenze, è rappresentata in

Yunyou Sanren 雲遊散人 e Huang Shang 黃裳

Huntian yitong xingxiang quantu 渾天壹統星象全圖 [Complete Celestial Chart] , China 1822

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Yunyou%201822.htm

La zona del Grande Carro nell'Orsa Maggiore nelle due mappe

La tavola viene esaminata anche nel monumentale lavoro di

Joserph Needham, Scienza e civiltà in Cina, Volume 3*, La matematica e le scienze del cielo e della Terra, I. Matematica e astronomia, pag. 340 ss, Giulio Einaudi Editore, Torino 1985

Puoi leggere anche il seguente articolo dedicato alla prima mappa celeste cinese:

The Dunhuang Chinese Sky, VII Sec. d. C., Cina

(Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 12:39-59,2009)

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Dunhuang%20VII%20sec%20base.htm

e

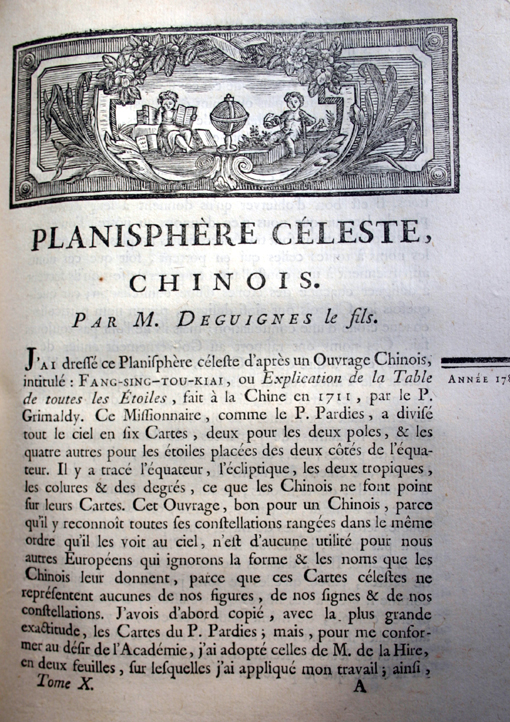

Claudio Filippo Grimaldi, Min Mingwo Dexian

Fang-sing-tou-kiai: Explication de les Tables de toutes les étoiles, Pechino 1711

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/grimaldi%201711.htm

e

Tae-Tsen-Hsun

Carta celeste e del Sistema Solare, Cina 1723 circa

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Thetsen%201723.htm

e

Gustav Schlegel

Uranographie Chinoise, Atlas Céleste Chinois et Grec d’après le Tien-Youen Li-Li, La Haye e Leyde 1875

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Schlegel%201875.htm

e

Jean-François Foucquet

Pro confirmatione systematis temporum propheticorum, hoc planispherium est in duplici, nempe in recto et in verso situ contemplandum. Hémisphère céleste boréal avec légende en chinois et annotations manuscrites en latin, Francia 1722 circa

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Foucquet%201822.htm

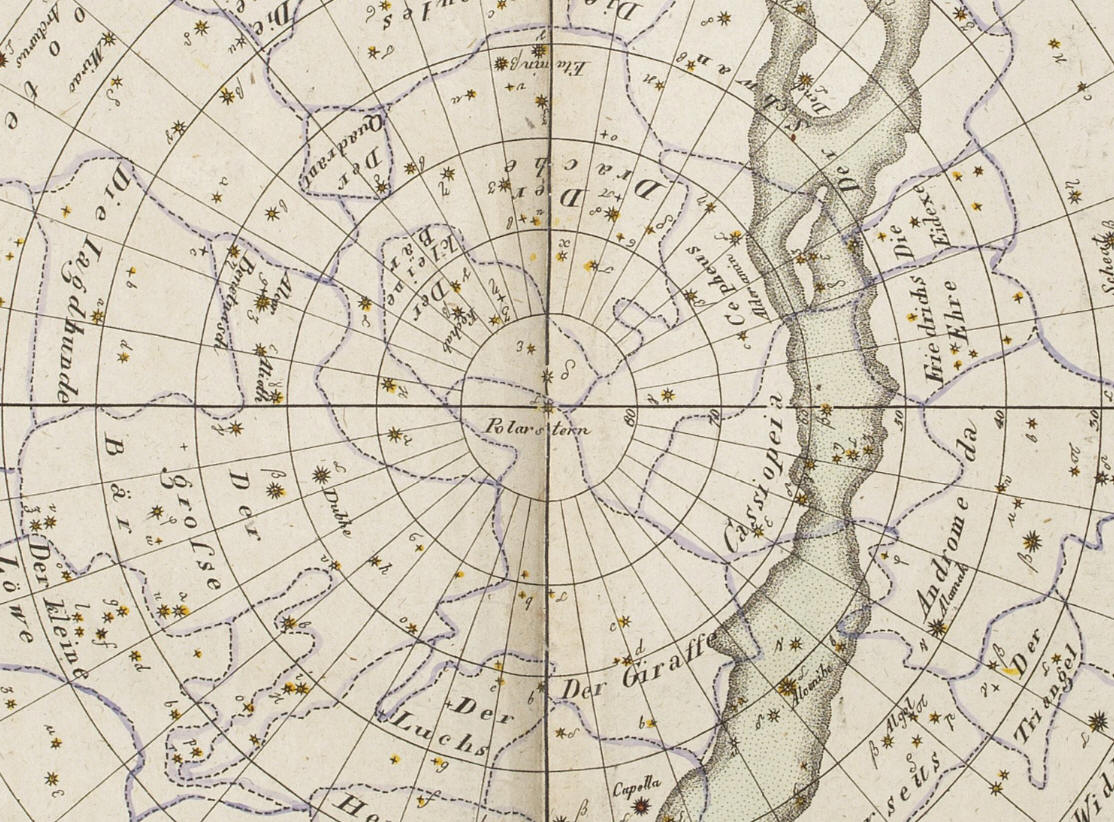

Nota conclusiva:

Per apprezzare lo spostamento delle stelle a seguito del fenomeno della precessione degli equinozi confronta la parte centrale della tavola cinese ( che di seguito ho opportunamente ruotata affinché il coluro equinoziale appaia esattamente da sinistra a destra) con una carta celeste del 1820: http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Fembo%201820.htm .

Tra le date di produzione delle due carte c'è una differenza di 630 anni, pari al 2,45% del ciclo completo di precessione degli equinozi di 25.720 anni, che equivale allo spostamento di 8,82° di tutte le stelle intorno al polo eclittico.

Lascio al lettore l'esercizio di identificare nelle due tavole la posizione del polo eclittico e di tracciare il cerchio intorno ad esso avente come raggio la distanza dal polo equatoriale (il centro delle due tavole). Il cerchio così prodotto è quello sul quale si sposta la proiezione del polo celeste equatoriale a causa del fenomeno della precessione degli equinozi. Identificare su tale cerchio della tavola celeste cinese la stella più vicina alla proiezione del polo equatoriale, identificare quindi, sempre sul perimetro delle stesso cerchio, la posizione della nostra Alfa Ursa Minoris e verificare se la distanza tra le due stelle sottende un angolo di 8,82°.

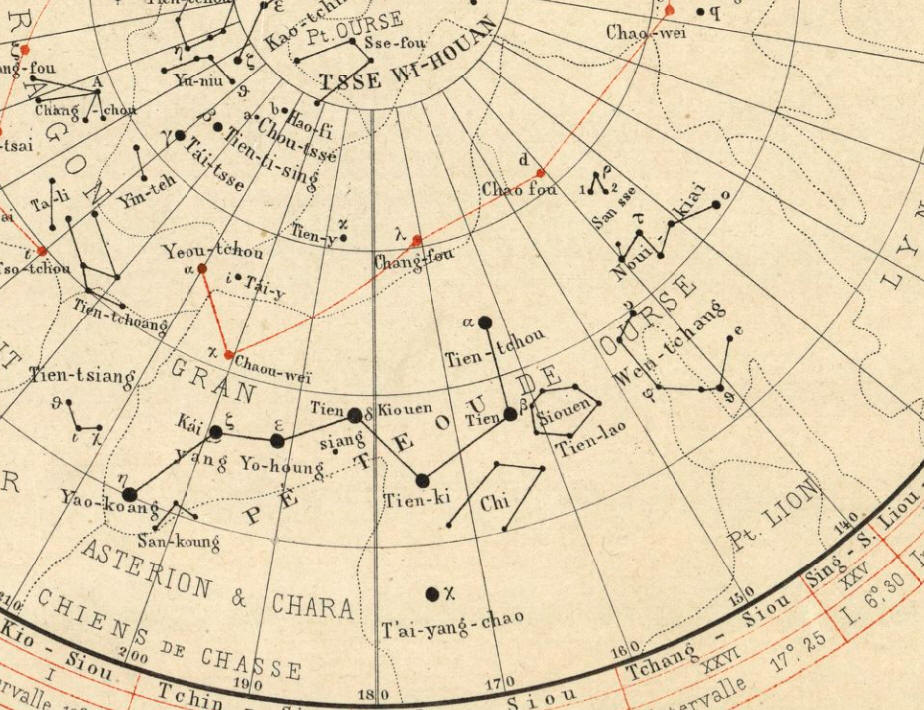

Sull'astronomia cinese, le costellazioni e la rappresentazione del cielo confrontati con il sistema occidentale puoi leggere:

Chrétien-Louis Joseph De Guignes

Planisphère céleste chinois. Partie Septentrionale. Paris 1785

Planisphère céleste chinois. Partie Meridionale, Paris 1785

in

Mèmoires de Mathematique et de Physique, Présentés a l'Académie Royal des Sciences, Par Divers Savans (Etrangers), Vol 10, Paris 1785

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Deguignes%20home.htm

di FELICE STOPPA

FEBBRAIO 2019