|

Elly Dekker |

Caspar Vopel's Ventures in Sixteenth-Century Celestial Cartography, 1532-1570 |

This paper concerns the

undertakings in celestial cartography of the sixteenth-century

Cet

article concerne les travaux en cartographie céleste du cartographe de

Cologne du XVIe siècle, Caspar Vopel. On

y décrit des exemplaires de son globe céleste imprimé ainsi que des cartes célestes figurées

sur sa mappemonde. La production de cartes célestes de Vopel montre son intérêt

singulier pour les mythes astronomiques à travers une série de caractéristiques

iconographiques remarquables. En particulier, l'introduction des constellations

d'Antinoüs et de la Chevelure de Bérénice (Coma Berenices en latin) se révèle

avoir été inspirée par une édition humaniste du catalogue des étoiles

de Ptolémée. Finalement, une étude des cartes célestes présentes sur les

copies de la mappemonde de Vopel par Valvassore (1558) et par Van den Putte

(1570) montre que ces copies reprennent différentes éditions de la carte

du monde de Vopel et que les cartes célestes présentes sur la mappemonde

de Matteo Pagano ont été copiées à leur tour à partir de celles de la

carte du monde de Valvassore.

Dieser Beitrag beschäftigt sich

mit der Himmelskartographie des Kölner Kartographen Caspar Vopel. Exemplare

seines gedruckten Himmelsglobus und der Himmelskarten, die sich auf seinen

Weltkarten befinden, werden beschrieben. Eine Reihe auffallender

ikonographischer Elemente auf Vopels Himmelskarten lassen sein außerordentliches

Interesse an astronomischen Mythen erkennen. Besonders seine Einführung der

Sternbilder Antinous und Coma Berenice wurden offensichtlich durch eine

humanistische Ausgabe des Sternkatalogs von Ptolemäus inspiriert. Darüber

hinaus zeigt die Untersuchung der Himmelskarten auf den Kopien nach Vopels

Weltkarte durch Valvassore (1558) und Van den Putte (1570), dass diese auf

unterschiedlichen Ausgaben von Vopels Weltkarte basieren und dass die

Himmelskarten auf der Weltkarte von Matteo Pagano von denen auf der Weltkarte

von Valvassore kopiert wurden.

Este artículo se centra en los proyectos de cartografía celeste del cartógrafo del siglo XVI Caspar Vopel, natural de Colonia. Se describen las copias impresas de su globo, y de los mapas celestes incluidos en su mapa del mundo. Los mapas celestes de Vopel muestran su extraordinario interés en los mitos astronómicos a través de una serie de llamativas imágenes. En particular la introducción de Vopel de las imágenes de Antinoo y Coma Berenice revela haber sido inspirada por una edición humanística del catálogo de estrellas de Ptolomeo. Por último, un estudio de los mapas celestes del mapa del mundo de Vopel, copiados por Valvassore (1558) y por Van den Putte (1570), muestra que esas copias son de diferentes ediciones del mapa del mundo de Vopel, y que los mapas celestes del mapa del mundo de Matteo Pagano fueron a su vez copiados de los del mapa del mundo de Valvassore.

Caspar Vopel (1511–1561) was born in Medebach, a small town not far from

In 1526 he entered the

Vopel became a well-known cartographer and was also active as an instrument

maker: (3)

Although his world map and his maps of Europe and the

This paper aims to fill in the gap

by describing Vopel's celestial globes and maps, with special attention given to

innovations introduced on their initations and derivatives.

In discussing Vopel's celestial cartography I follow existing conventions

and denote constellations by their Latin names. Subgroups, such as the Pleiades,

are referred to by their English names. Stars are identified in one of two ways:

by modern convention or by the serial number from its Ptolemaic constellation.

Thus Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, is denoted as α Leo or Leo 8.

Unformed stars of a constellation, listed by Ptolemy separately after the

‘formed’ stars because they are located outside the imaginary constellation

figure, are numbered as 1e, 2e and so on, with ‘e’ standing for external.

Thus the first of the unformed stars of Leo is Leo 1e, the second Leo 2e. (5)

The lasting merit of Vopel's printed globe and maps—or so it appears in retrospect—is the images of two star groups, Antinous and the Lock of Hair, better known as Coma Berenices, neither of which had previously been represented graphically. Their introduction on Vopel's printed globe of 1536 started a process by which the two groups came to be recognized as individual constellations. Since then, many other new constellation figures have been added to the celestial sky, sometimes for unformed stars in the northern hemisphere, at other times for stars newly recorded in the southern sky during voyages of exploration. The impact of Vopel's initiative raises a number of questions including why Vopel introduced the images of Antinous and Coma Berenices and what the reaction of his contemporaries was. Before dealing with these questions, however, we need to look at Vopel's various undertakings in celestial cartography.

https://www.kulturelles-erbe-koeln.de/documents/obj/05741337

Vopel's earliest surviving piece of

work is his manuscript celestial globe of 1532, now in the Kölnisches

Stadtmuseum. (6)

It has a diameter of some

Like all globes made in the Renaissance, Vopel's presents the 1025 so-called

fixed stars described in the star catalogue in Ptolemy's Syntaxis mathematica,

a second century ad astronomical work devoted to

the motions of the wandering stars, or planets. (8)

The fixed stars, discussed in books

VII and VIII, serve in this context as a reference grid for locating the planets.

The star catalogue is organized as follows:

For each star (taken by constellation), we give, in the first section, its

description as a part of the constellation; in the second section, its position

in longitude, as derived from observation, for the beginning of the reign of

Antoninus…; in the third section we give its distance from the ecliptic in

latitude, to the north or south as the case may be for the particular star; and

in the fourth, the class to which it belongs in magnitude. (9)

The recorded star positions are

valid for the epoch 137 ad, the beginning of the

reign of Antoninus. Since precession causes the equinoxes (the points of

intersection between the ecliptic and the equator) to drift slowly with respect

to the stars in the course of time, the stellar longitudes have to be adapted

for later times.

Ptolemy's Syntaxis mathematica was transmitted to the Latin West

through Arabic translations circulating in Muslim Spain. The Latin translation

made from the Arabic around 1175 by Gerard of Cremona became known in the Middle

Ages as the Almagest; it was first printed in 1515. The epoch of the

catalogue in Gerard's translation was ad 137.

(10)

The star catalogue in the wording of Gerard's translation could also be

found appended to the Latin version of the Alfonsine Tables, a

much-copied work consisting of tables for calculating the positions of the

planets. This ‘Alfonsine catalogue’ is adapted to the epoch 1252 (the

beginning of the reign of King Alfonso X of

The astronomical nomenclature in

the Arabic-Latin catalogue version was understandably permeated with names

originating in transliterations from the Arabic. This Arabic legacy is

recognizable in the hand-written notes on Vopel's manuscript globe. Although

many details are hard to read, and a complete description is still a desideratum,

I can quote, as an example, the text for the constellation

|

The second name given to the

constellation, vultur volans, reflects the indigenous Arabic name used in

the 1515 edition of Ptolemy's star catalogue. (12)

The star name alkaÿr does not occur in that catalogue, however, but

stems from an Arabic-Latin tradition connected with the construction of

astrolabes that goes back to the 980s. (13)

Vopel may have taken this name from the star table in Johannes Stöffler's

influential Elucidatio fabricae ususque astrolabii. (14)

The astrological characteristics of the fixed stars were expressed by means

of the influences thought to be exerted by the planets. Vopel probably obtained

his information from the astrological survey of the fixed stars, Nomina &

qualitates stellarum fixarum secumdum Ptol[lemeum], which was added to the

1524, 1545 and 1553 editions of the Alfonsine Tables. (15)

The names Anhelar and Abrachaleus

for the brightest stars of Gemini (α and β Gem), inscribed on Vopel's

manuscript globe, are not mentioned in the 1515 edition of the star catalogue,

but they are found in the astrological survey in the Alphonsine Tables,

and their use here shows that Vopel knew the Tables.

A number of names on Vopel's manuscript globe cannot be explained by any

source material from the Arabic-Latin tradition. Take, for example, the name Antinous

inscribed below the head of

Its earliest appearance was in the Latin translation made about 1451, at the

request of Pope Nicholas V, directly from the Greek by the humanist George of

Trezibond, or Trapezuntius (1395–1484). The first printed edition of

Trapezuntius's translation appeared only in

Trapezentius's humanist version of the star catalogue differs from Gerard of

Cremona's Latin translation from the Arabic by the use of what humanists

considered ‘good’ Latin. In the translation by Trapezuntius one searches in

vain for names developed from Arabic transliteration. The name Vultur volans,

for

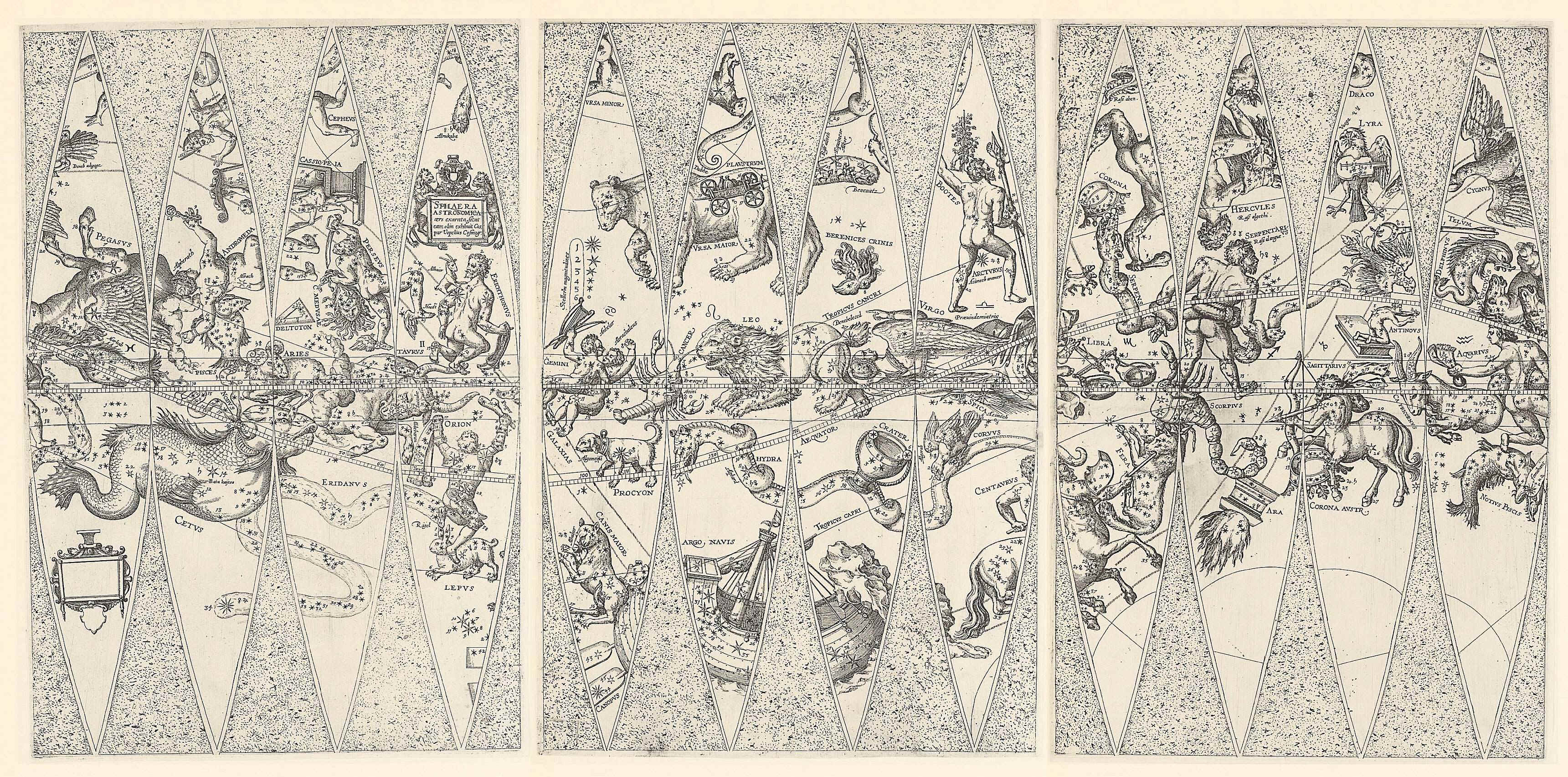

For his figures of the forty-eight constellations Vopel copied the style and

iconography of the pair of maps produced by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528),

Conrad Heinfogel (1470–1530) and Johann Stabius (d. 1522), and published in

1515. (19)

The iconography of what are usually referred to as Dürer's maps, because it

was he who cut the wood blocks, proved extremely successful throughout the

sixteenth century. It served as the model for the planisphere published by Peter

Apian (1495–1552) in 1536 and reprinted with a different type set in his Astronomicum

Caesarum in 1540. (20)

Planisferi di Conrad Heinfogel (?)

Die Karte des Nördlichen Sternenhimmels, Inv.-Nr. Hz 5576

Die Karte des Südlichen Sternenhimmels, Inv.-Nr. Hz 5577

Petrus Apianus

Astronomicum Caesareum, Ingolstadt 1540

Dürer's figures were also used on the printed celestial globe of 1537

produced by Gemma Frisius (1508–1555) together with Gaspar van der Heyden (c.1496–after

1549) and Gerard Mercator (1512–1595), and on the manuscript celestial globe

made under the supervision of Johannes Praetorius (1537–1616) in 1566. (21)

Belgian celestial table globe, 1537, by van der Hayden, Frisius and Mercator. Royal Museums Greenwich

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/19822.html

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Gemma%201537.htm

(vedi in Atlascoelestis:)

Gaius Iulius Hyginus

C. Ivlii Higini, Avgvsti Liberti, Poeticon Astronomicon : Ad Vetervm exemplarium eorumq[ue] manuscriptorum fidem diligentissime recognitum, & ab innumeris, quibus scatebat, uitiis repurgatum, Coloniae 1534

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Hyginusvopel%201534.htm

Vopel's next undertaking in

celestial cartography was the series of forty woodcut constellation images made

for the 1534 edition of the Poeticon Astronomicon, published by the

Cologne humanist and printer Johannes Soter. (22)

This astronomical treatise on the rudiments of astronomy is attributed to

the librarian of the Roman emperor Augustus, C. Iulius Hyginus (first century bc).

Vopel's involvement in Soter's edition is expressed in an address to the reader

printed at the end of the book. He also included a reference to his woodcut

illustrations of Hyginus's Poeticon Astronomicon in a legend on his world

map. (23)

Cycles of individual constellation images are seen in many medieval

manuscripts, where they illustrate so-called descriptive star catalogues, that

is, written lists of the locations of stars within constellation images. The

oldest extant copies of such lists date from the beginning of the ninth century.

Some descriptive star catalogues are part of the scholia of Latin translations

of the Phaenomena, the earliest surviving Greek description of the

celestial sky by Aratus of Soli (c. 310–240/239 bc);

others occur in treatises of the ‘computus’. (24)

Book III of Hyginus's Poeticon

Astronomicon contains such a descriptive star catalogue.

The most common cycle of constellation images printed in the Renaissance is

the one illustrating the editio princeps of the Latin translation of

Aratus's poem by Germanus Iulius Caesar (15 bc–19

ad). This was published in

The woodcuts of the Scot illustrations were also used in the 1482 and 1485

editions of Hyginus's Poeticon Astronomicon, published by Erhard Ratdolt

in

In contrast, the

The images of Andromeda in the editions by Ratdolt and Soter of respectively

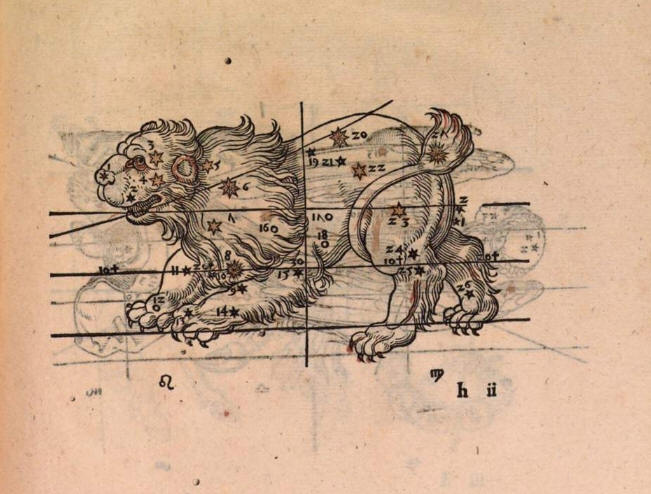

1482 and 1534 are shown in Figure 2 The 1482 image depicts Andromeda as a male/female

with outstretched arms tied to the branches of trees. (27)

The stars plotted in the constellation are in keeping with Hyginus's

descriptive star catalogue. Vopel's image on the other hand follows Dürer's

design of a naked woman in chains. He placed the constellation in relation to

sections of a number of celestial circles: great circles through the ecliptic

poles separating the signs of the zodiac, the Tropic of Cancer and the

equinoctial colure. In the absence of declination scales it is not possible to

decide what sort of projection Vopel used, but it certainly was not

stereographic. The great circles through the ecliptic poles in the woodcuts in

Soter's Poeticon Astronomicon seem to represent the boundaries of globe

gores and clearly anticipate Vopel's printed globe. It is, therefore, not

surprising that the stars in Vopel's figure of Andromeda do not follow Hyginus's

descriptive star catalogue, but are based on Ptolemy's positions and magnitudes

of the stars and are numbered according to their order in his star catalogue.

(28)

|

The principles underlying Vopel's

woodcut of Andromeda hold for the other constellations. A few, however, diverge

from the general pattern. For example, the iconography of Boötes deviates from

Dürer's design in that Boötes now holds a sickle in his raised left hand, a

detail that Vopel borrowed from the Scot illustration, where Boötes is

portrayed as a farmer (Fig. 3).

|

Fig.

3.

Boötes from two editions of Hyginus, Poeticon Astronomicon.

Woodcuts. Left, the Radolt edition of 1482, portraying Boötes as a farmer.

Right, the Soter edition of 1534, where Boötes holds a sickle in his

raised left hand, a detail borrowed from the illustration in the Radolt

edition. (Reproduced with permission from the History of Science

Collections,

|

In some constellations unformed

stars or stars belonging to a neighbouring constellation are found. For example,

the image of Corona Borealis contains some stars from Serpens (Ser 1–3,

5–6), and included in the outline of Taurus are two non-Ptolemaic stars (numbered

34 and 35 and placed after the Ptolemaic Pleiades stars 30–33) and the Greek

names of the Pleiades and the Hyades (Fig. 4). Hyginus discussed the Pleiades in

a separate entry in Book II.21, declaring that only six of its seven stars were

discernable. This could explain why Vopel increased the four Ptolemaic Pleiades

stars to six. The one star name shown in Vopel's drawings, CANOPVS in

Navis, is also discussed by Hyginus, although not in his entries on Navis (Books

II.37 and III.36) but in the entry on Eridanus (Book II.32). All this suggests

that the images were taken from something much larger, such as a set of globe

gores. The rough scale (in units of 10°) for longitudes that accompanies the

drawings of the zodiacal constellations is consistent with this thesis.

|

Since

the Ptolemaic stellar configurations of Vopel's constellation cycle are not in

line with Hyginus's descriptive star catalogue, the series must have confused

readers trying to connect the text with the images. This did not, however,

prevent the reproduction of either the whole cycle or part of it in a number of

astronomical works printed later in the sixteenth century. (29)

(Nota di Atlascoelestis):

Si pensa che gli stessi stampi in legno di Vopel siano atati utilizzati nell'officina tipografica di Theodorus Graminaeus per stampare le xilografie delle costellazioni utilizzate per l'edizione del 1569 e 1570 (vedi: https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=graminaeus-1569) , di

Arati Solensis

PHAENOMENA ET PROGNOSTICA. Interpretibus M. Tullio Cicerone, Rufo Festo

Avieno, Germanico Caesare, Una cum Eius Commentariis. C.

Iulii Hygini Astronomicon...

Coloniae Agrippinae (

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Aratus%20Solensis.htm

L'opera può essere consultata

nella seguente pagina

per cortesia di

http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000000204

e per cortesia di

in

https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/resolve/display/bsb10139476.html

Vedi: https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj05741338 e http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Anonimo%20vopel%201536%20base.htm, nota di Atlascoelestis

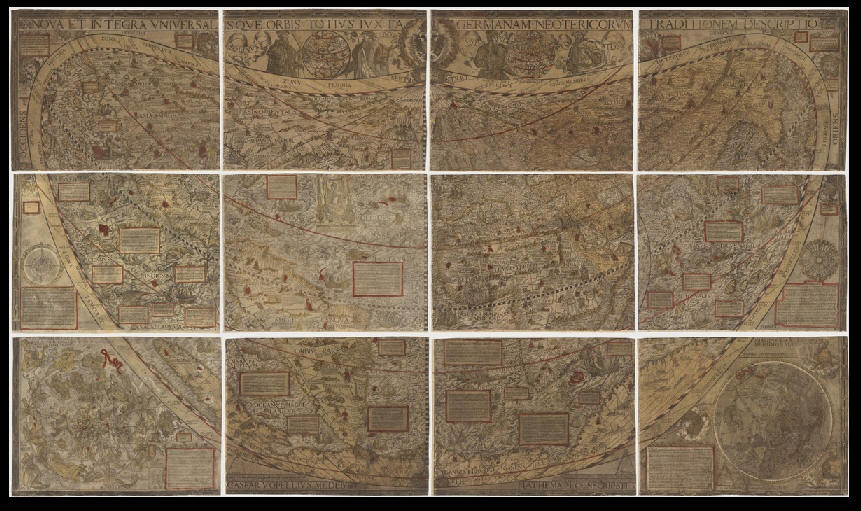

Vopel's manuscript globe of 1532

and his series of woodcuts of 1534 supposedly served as trials for the

production of the woodcut gores for his printed globe with the inscription: CASPAR.

VO/PEL. MEDEBACH / HANC. COSMOGRA: / faciebat sphæram. / Coloniæ. A°. 1536

(Fig. 5). The design of this globe (described in Appendix 1 as G1) follows in

many respects that of the earlier manuscript globe. Its nomenclature, however,

is less extensive, presumably because it is easier to make handwritten notes

than to cut lengthy texts in wood. Thus

Vopel's example was followed on the

celestial globe of 1537 by Gemma Frisius and his collaborators and on that of

1551 by Gerard Mercator. (31)

|

A comparison of Vopel's manuscript

globe with the printed one shows changes in the stellar positions. For example,

the stars in the tail of Aries (Ari 9–10) lie south of the ecliptic on the

manuscript globe but north of it on the printed one. The star at the end of the

chain of Andromeda (And 23) stands in the middle of the sign of Aries on the

manuscript globe and at the beginning on the printed globe. On Vopel's woodcut

of Aries in the 1534 edition of Hyginus, the stars Ari 9–10 are still shown

south of the ecliptic, whereas on the woodcut of Andromeda the star And 23 is

located at the beginning of the sign of Aries (see Fig. 2). Such variations in

position show that Vopel was continuously adapting his mapping.

Positional differences are not

necessarily the result of careless work by the mapmaker but may reflect the use

of a specific version of the Ptolemaic catalogue. Comparable variations are

noticeable in contemporary sources. On Dürer's maps (1515), Apian's

planispheres of 1536 and 1540, and Gemma Frisius's celestial globe of 1537, the

stars Ari 9–10 are south of the ecliptic and the star And 23 is in the middle

of the sign of Aries. On the globe gores cut in wood in 1515 by Johannes Schöner

(1477–1547) and on Mercator's globe of 1551 the stars Ari 9–10 are north of

the ecliptic and the star And 23 is at the beginning of the sign of Aries.

The most important characteristic

of Vopel's printed globe is a series of iconographic peculiarities that do not

derive from Dürer's maps. They also do not occur on the manuscript globe or on

the woodcuts in the 1534 edition of Hyginus. This series is comprised by images

for Antinous and Coma Berenices, Boötes accompanied by hunting dogs and a goat

eating leaves from a vine above his head, the Wagon (Plaustrum) in the

body and tail of Ursa Maior, the Kids (Haedi) in Auriga, six tiny female

heads illustrating the Pleiades (Vergiliae) in Taurus, two Asses (Asini)

in Cancer, Lyra as a bird with a stringed instrument placed horizontally over

its body, and one of the Gemini with a lyre or a similar instrument with bow.

These features are discussed separately below.

Vopel's printed globe attracted a number of imitators. Two sets of

copperplate gores and one set of mounted woodcut gores (described in Appendix 1,

G2–G4) appear to be close copies of Vopel's printed globe. (32)

The anonymous engraver of the G2

gores acknowledged his source: SPHAERA / ASTRONOMICA / aeri exarata, sicut /

eam olim exhibuit Cas/par Vopelius Cosmogr. (Fig. 6). It is tempting to

identify these G2 gores with those used for making the celestial globe of the

pair by Johannes Antonii Barvicius reported to have been published in

|

Fig.

6.

Gores of an anonymous copy of Vopel's printed globe of 1536 (G2 in

Appendix 1). The enlargements 1 to 4 show, respectively, the small images

of the Pliades, the Kids, the Lyre of the western Twin, and the Asses.

Sotheby's, Catalogue Natural History, Travel, Atlases and Maps (

|

The makers of the G3 copperplate

gores and the G4 globe do not mention Vopel. A comparison with Vopel's printed

globe shows that the G3 gores were not copied particularly carefully and may

well have been the work of an amateur. The engraver has omitted the names of

five constellations and given only one of the star names marked on Vopel's

printed globe (see Appendix 1, G3). The G4 celestial globe belongs to a pair of

which the terrestrial globe does not follow any of the editions of Vopel's

terrestrial globe. The G4 gores are woodcuts, as are those of Vopel's printed

globe. The maker included only five star names, two of which do not stem from

Vopel's globe (see Appendix 1, G4). The most striking deviation from Vopel's

1536 globe is the image of a young man representing Phaeton placed at the end of

Eridanus, which is first seen on the copperplate celestial globe gores by François

Demongenet, published around 1560. (34)

Il globo celeste di Vopel del 1536 ha ispirato anche quello prodotto da Christoph Schissler ad Augusta nel 1575, diametro 42cm:

“CHRISTOPHORVS SCHISSLERVS AVGVSTANVS GEOMETRICVS ET ASTRONOMICVS FABER GLOBVM HVNC CÆLESTREM FACIEBAT ET DESCRIBEBAT ANNO DOMINI 1575”

“STELLÆ HVIVS GLOBI NVMERATÆ AC DISTRIBVTÆ SVNT SECVNDVM CVRSVM SPHÆRÆ OCTAVÆ AD NOSTRVM TEMPVS ANNVMQVE ACCOMMODATÆ 1575“

https://www.parquesdesintra.pt/pontos-de-atracao/globo-celeste/

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=schissler-1575

E ha anche ispirato un globo in rame di 29 cm di autore anonimo e di epoca imprecisata ora esposto al

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/19782.html

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=anonym-15xx

https://www.astronomie-nuernberg.de/index.php?category=duerer&page=nachfolger

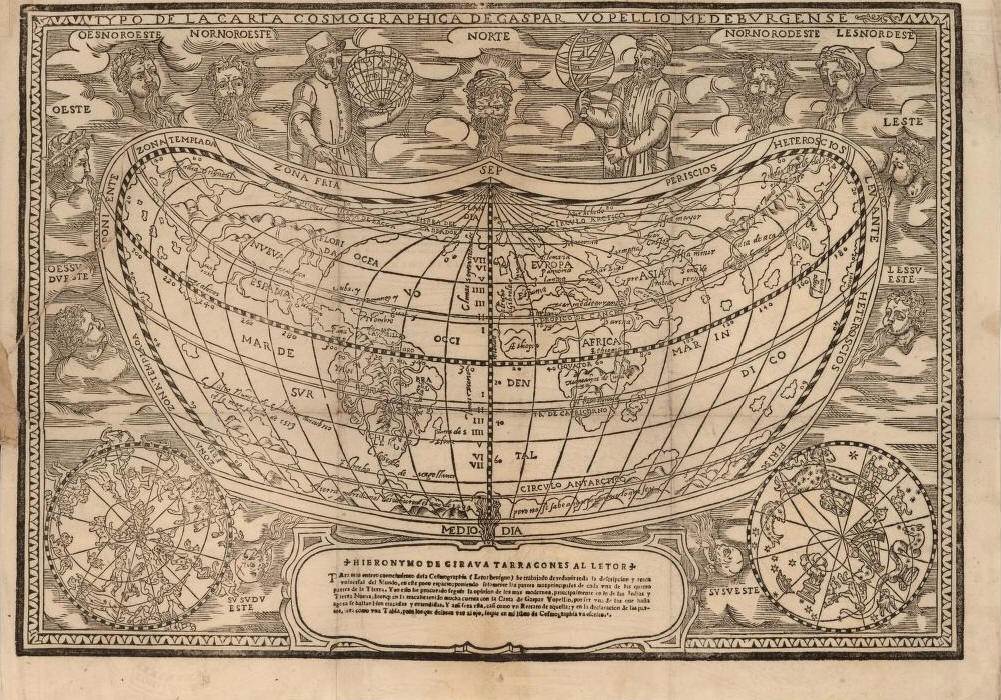

In 1545 Vopel published a world map

in which the northern and southern celestial hemispheres occupy, respectively,

the lower left and right corners. (35)

A second edition was published in 1549, and further editions may have

appeared in the 1550s. (36)

No example of Vopel's world map has survived, but a number of derivatives

are known. The celestial maps on these are described in Appendix 2 as M1, M2 and

M4. (37)

The celestial maps (M1) on the

world map by Jeronimo de Girava of 1556 are only rough copies and show just

enough detail to make the model recognizable. A much better impression of

Vopel's celestial maps is obtained from the close copies of his world map by

Giovanni Andrea Valvassore (M2) of 1558, shown in Plates 7 and 8, and by

Bernaard van den Putte (M4) of

At first sight the celestial maps on Valvassore's and Van den Putte's world

maps seem to be no more than copies of Dürer's maps. Valvassore and Van den

Putte reproduce the titles along the top and the images of Aratus, Manilius,

Ptolemy and al-![]() ūfī

that are found in the corners of Dürer's northern hemisphere. However, the maps

are not slavish copies of Dürer's. The stars on Valvassore's and Van den

Putte's celestial maps are coded on a six-point scale given on the map ( Fig. 7)

according to their brightness. Many stars are named and accompanied by planetary

symbols. Valvassore's and Van den Putte's celestial maps include a number of

names not seen on Vopel's printed globe. For example, three names (Βασιλισκος

/ Regulus / Cabalezet) for the bright star α Leo are added. The

first and the last of these names stem from respectively the Greek and Arabic

tradition. The name Regulus is a concoction of the early sixteenth

century humanist astronomers. (38)

ūfī

that are found in the corners of Dürer's northern hemisphere. However, the maps

are not slavish copies of Dürer's. The stars on Valvassore's and Van den

Putte's celestial maps are coded on a six-point scale given on the map ( Fig. 7)

according to their brightness. Many stars are named and accompanied by planetary

symbols. Valvassore's and Van den Putte's celestial maps include a number of

names not seen on Vopel's printed globe. For example, three names (Βασιλισκος

/ Regulus / Cabalezet) for the bright star α Leo are added. The

first and the last of these names stem from respectively the Greek and Arabic

tradition. The name Regulus is a concoction of the early sixteenth

century humanist astronomers. (38)

Other names, such as the two in

Eridanus, Acarnar and Angetenar, appear to stem from the star

catalogue appended to the Alfonsine Tables. Especially striking is the

addition of Greek names for many constellations (

|

Fig.

7.

Table with the marks for stars with magnitudes 1 to 6, together with the

number of stars in each magnitude class, in the right lower corner on

northern celestial hemisphere from the world map by Giovanni Andrea

Valvassore (

|

|

||

|

|

Many but not all the iconographic

peculiarities introduced on Vopel's printed globe seem to have been reproduced

on the celestial maps on his world map, when judged by its copies. All maps M1

to M5 contain the images of Coma Berenices and Antinous. M1 to M4 depict Boötes

with sickle, club and dogs, and M2 to M4 also have the vine-eating goat. Missing

on all the maps (M1–M5), and very likely also on Vopel's, are the Wagon in

Ursa Maior, the Pleiades, the Kids and the Asses. The last three images may have

been too tiny to be added to a map, and presumably these images were already

lacking on Vopel's map. The absence of the Wagon may have been provoked by the

polar stereographic projection of the celestial maps, which results in some

congestion of the constellations around the North Pole. This could also explain

why the name of the Wagon (Plaustrum) is found near the head instead of

near the tail of Ursa Maior. However, the new location of the name Plaustrum

may derive from Apian's planispheres of 1536 and 1540, from which the non-linear

scale for measuring latitudes was borrowed.

All the celestial maps (M1–M5) display two iconographic characteristics

that define them as a group and that are not found on Vopel's globes. One is a

cloud of smoke rising from the flames on top of the altar of Ara; the other is a

swimming female at the end of Eridanus (see Plate 8). Medieval illustrations of

Eridanus associate the constellation with the river god, and this is how

Eridanus is depicted in the 1482 edition of Hyginus. (39)

In some editions of Hyginus's fables, however, the figure at the end of the

river is a swimming maiden; this is what we find on Apian's planispheres of 1536

and 1540, on the globe of Gemma Frisius of 1537, on the globe gores of Georg

Hartmann of 1538, and on Demongenet's woodcut gores of 1552. (40)

The popularity of the swimming

maiden at the end of Eridanus may have been the reason why Vopel decided to

introduce it on his celestial maps of 1545.

|

It is not a priori clear how the

various copies of Vopel's celestial maps are interrelated. Since the world maps

of Valvassore and Van den Putte are close in content, it has been suggested that

Van den Putte's world map was based on the earlier one of Valvassore. (41)

Details in the nomenclature of the celestial maps, however, show that the

two world maps may be independent copies. For example, on Van den Putte's

celestial maps (M4), one finds the Greek name of the Gemini, the four Ptolemaic

and the two extra non-Ptolemaic stars of the Pleiades and their Latin name Vergiliae,

the Latin Hædi for the Kids in Auriga, and the star names Alhabor

(α CMa) and Bellatrix (α Ori). None of these names occurs on

Valvassore's copy (M2). The same features are missing from the celestial maps of

Pagano (M3). Valvassore's and Pagano's celestial maps also share a number of

spelling errors, for example, Makab (α Peg) instead of Markab,

which do not occur on Van den Putte's map. Since Pagano's maps are less complete

than those of Valvassore, the common omissions and spelling errors suggest that

Pagano used the celestial maps on Valvassore's world map as his model and not

the other way round. His world map should therefore be dated later than 1558.

(42)

Another detail concerns the image

of Lyra. On the copies of Vopel's celestial maps Lyra is depicted with the

stringed instrument arranged vertically as on Dürer's maps instead of

horizontally as on Vopel's printed globe. Although it is hard to say why Vopel

should have returned to Dürer's Lyra, the change is not particularly

significant, since this is the way Vopel had already depicted Lyra on his

Hyginus drawing and on his manuscript globe (see Fig. 1). What is of interest

here is that on three maps (M1–M3) the bird is now headless, which suggests

that this was a characteristic of the models used for these maps. The presence

of a ‘headed’ bird on Van den Putte's celestial maps, together with the

additional names and the Pleiades stars, suggest that Van den Putte used one of

the later editions of Vopel's world map with alterations made by Vopel himself.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that no other Renaissance celestial maps

are known that offer as many details as Vopel's, when judged by its copies. The

addition of celestial maps on a world map is another matter. (43)

This was not merely symbolic, but a

gesture designed to present a complete image of the cosmos. The concept must

have appealed to Renaissance mapmakers, since later in the sixteenth century

Vopel's example was followed by many mapmakers besides those copying his world

map. (44)

As already noted, Vopel's printed

globe of 1536 is characterized by a series of conspicuous iconographic features

that are discussed here in greater detail. The features are not of equal

importance. Some, such as the tiny figures of the Pleiades, the Asses and the

Kids, are more like mythological footnotes in the iconographic landscape (see

Fig. 6). These star groups were recognized early in Greek astronomy, and images

of them in medieval illustrated manuscripts are not unknown, but I have never

seen the Pleiades and the Asses represented graphically on any other celestial

globe, and the Kids are only on globes postdating Vopel's printed globe. (45)

The lyre held by the western twin in Gemini is another minor feature (see

Fig. 6). The names Anhelar (α Gem) and Abrachaleus (β

Gem) indicate that Vopel had identified the Gemini as Apollo and Hercules, the

Latin names of which were added on Vopel's celestial maps (see Plate 7 and

Appendix 2). (46)

Vopel emphasized this identification by giving the western twin the lyre,

thus recalling the well-known myth that Hermes offered Apollo the lyre as

compensation for his attempt to steal Apollo's herd. (47)

On Schöner's woodcut globe gores of 1515 the western figure in the Gemini

has a violin-like instrument as an attribute that is seen also on his later

globe of c.1533, where he added the star names Apollinis and Herculis.

(48)

The mythological background for the

iconography of Boötes is more complicated. This classical hero is represented

on Vopel's printed globe as a naked bearded man with a sickle in his raised left

hand and a lance in his right hand (Fig. 8). On his right side is a pair of dogs

on a lead, which he holds in his right hand. Above his head is a goat eating

leaves from a vine. The 1534 woodcut of Boötes (see Fig. 3) can account for the

main figure holding a lance in the one hand and a sickle in the other, but where

did the other features come from?

|

Fig.

8.

Boötes on Vopel's printed globe of 1536. (Reproduced with permission from

the Director of the Graphische Sammlung of the Kölnische Stadtmuseum.)

|

The image of a vine with the

leaf-eating goat finds its origin in the myth connecting Boötes with Icarius.

This story survives today only in Book II.4 of Hyginus's Poeticon

Astronomicon:

Many say that this [the constellation Boötes] is Icarius, the father of

Erigone. To him, because of his justice and piety, Liber granted wine, the vine,

and the grape, so that Icarius might show mankind in what way the vine should be

cultivated, what grows from it, and when it is grown, how it should be used.

When he had planted the vine and by diligent pruning made it sprout, it is said

that a goat fell on the vine and picked off all the tender leaves it found there.

Icarius became so irritated that he killed the goat, made a bag out of its skin,

filled the bag with air then tied it, and throwing it among his companions

ordered them to dance around it. And so as Eratosthenes says, ‘Men first

danced around the goat of Icarius’. (49)

Some scholars believe that Hyginus took this story from a lost poem, Erigone,

by Eratosthenes describing the drama of Icarius. (50)

The main story, also told by

Hyginus, relates how Icarius, after receiving the gift of wine, completely

filled an ox-cart with wineskins and offered the wine to shepherds all around

The first stage of the story is depicted in a mosaic in the House of

Dionysus, in Nea Paphos in

Vopel has here combined the story of Icarius with another tale connected

with the seven stars of Ursa Maior, known in antiquity as the Wagon or Wain or

by its Roman name Plaustrum. (52)

|

Fig.

9.

Panel with Dionysos (on the left) presenting the gift of wine to Icarius

(in the middle) who holds the reins of an oxcart filled with wineskins. On

the right are two shepherds, the first wine drinkers according to the

inscription, who became drunk after tasting the gift. From a mosaic in the

House of Dionysus, in Nea Paphos in

|

|

Hyginus also mentions this star

group in his description in Book II.2 of myths related to Ursa Minor.

Those who first observed the heavens and assigned the stars to a particular

figure named this constellation the Wagon, not the Bear, because two of its

seven stars, being similar and very close together, are said to be oxen, while

the remaining five resemble a wagon. For this reason, those who assigned names

wished to call the sign closest to that constellation Bootes. (53)

Vopel's image of a four-wheeled cart pulled by three horses instead of oxen

is not completely in line with this classical description. The horse-drawn cart

recalls the (mirror) image of the Wagon in various publications of Peter Apian

from 1524 onwards, where it served to illustrate how to find the location of the

pole star (Fig. 11). (54)

In addition to the seven stars of the Wagon, the stellar configuration

includes a faint star (80 / g UMa) not recorded in the Ptolemaic catalogue. This

faint star is placed adjacent to the bright Ptolemaic star (UMa 26 / ζ UMa)

above the middle horse (close to the letter H) labelled ALCOR. In the

text accompanying Apian's Wagon, the faint star is referred to by its German

name ‘Reiterlein’ (the driver). (55)

On Vopel's globe the faint star is not marked, but the slightly differently

spelled Arabic name Alkor and the Latin name of ‘Reiterlein’—Equitator—are

placed above the rider on one of the horses, as if they are meant to refer to

this image rather than to a specific star (see Fig. 10). (56)

Vopel's use of Apian's works, in

particular of his Quadrans astronomicus of 1532 or his Instrument Buch

of 1533, is underlined by the presentation of Lyra as a bird with a

stringed instrument across its body (Fig. 12). (57)

|

|

The remaining attribute of Boötes

to account for is his dogs. (58)

The myth connecting Boötes with Icarius does not apply, since it mentions

only one dog, Maera, which is to be identified with Canis Minor. (59)

Boötes's two dogs may have emerged from an attempt to make sense of a

difficult phrase in Gerard of Cremona's Ptolemaic star catalogue of Boo 8 (μ

Boo), although we have no direct evidence to support such a hypothesis. (60)

Be that as it may, Boötes's dogs were not uncommon in the Renaissance. Two

dogs are part of the image of Boötes as a young man in the fifteenth-century

illustrated manuscript in

Two dogs are also portrayed on Stöffler's celestial globe of 1493, and on

Schöner's wood-cut globe gores of 1515. (62)

Apian included two dogs as part of Boötes on the unusual celestial map

published in his Horoscopion generale of 1533 and three dogs on the

planispheres of 1536 and 1540. (63)

Thus the dogs had become a regular

feature of the iconography of Boötes on maps and globes by the time Vopel

published his celestial globe.

Rather more central to the present discussion than these features are

Vopel's images for the Lock of Hair and Antinous. Coma Berenices comprises three

unformed stars (Leo 6e–8e) described in the Ptolemaic catalogue as part of the

nebulous mass called Πλóκαμος (Lock of Hair)

between the edges of Ursa Maior and Leo (Fig. 13). (64)

Legend has it that the Lock of Hair

was placed among the stars by Conon the mathematician (fl. 245 bc)

to sooth Ptolemy III Euergetes of Egypt, whose wife Queen Berenice II (273–221

bc) had made a votive offering of a lock of her

hair for his safe return from war. When Ptolemy arrived home, the lock was

placed in the temple but, alas, on the following day it could not be found and

the loss greatly upset the king.

|

The drama was described by the

Alexandrian poet Callimachus (first half of the third century bc)

in a poem of which only a fragment survives. It remained known through a Latin

version by the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus (c.82–c.52 bc).

(65)

A pupil of Callimachus, Eratosthenes (c.276–c.195 bc),

included the story in a now-lost work on constellation myths, of which only an Epitome

survives today. (66)

The legend is also recorded in Hyginus's Poeticon Astronomicon. (67)

Although Berenice's Lock of Hair is thus well attested in literary sources,

no images of it are known before Vopel put it on his globe. (68)

The little female figure shown in the centre of the lock (see Fig. 13)

presumably represents its personification as expressed in Catullus's poem:

‘that same Conon saw me on the floor of heaven, / me a lock from the head of

Berenice’. (69)

A similarly prominent myth adopted by Vopel concerned Antinous, the

figure composed of the six unformed stars (Aql 1e–6e) below

This asterism is believed to have been introduced by the Roman emperor

Hadrian (76–138 ad) in honour of his favourite,

Antinous. This young man had been born in the Roman

|

Although Ptolemy did not tell the

story of Antinous, his star catalogue is the only known astronomical work to

mention the name. As a contemporary of Hadrian, Ptolemy must have been well

acquainted with the many statues and coins that surrounded the deification of

Antinous. (72)

One reason for the absence of Antinous's story from the corpus of

astronomical legend that dominated the Middle Ages may be the relative lateness

of the episode in Roman history. Another could be Christian ideas of retribution

for the emperor's presumed unlawful pleasures. (73)

Whatever the explanation, the fact

remains that the image of Antinous was lacking from celestial cartography until

Vopel added it to his representation of the sky. Moreover, Vopel's image does

not allude to Antinous as an ephebe but shows him just before the dramatic act

of drowning himself, an image that was without precedent and that may have been

invented by Vopel himself.

Legend and myth, we see from these

paragraphs, are common denominators in the series of iconographic peculiarities

introduced by Vopel on his printed globe. They reflect his use of a wide variety

of sources: Hyginus's Poeticon Astronomicon, contemporary works by Peter

Apian, books on history recounting the story of Antinous and the poem by

Catullus describing Berenice's lock of hair. The invention of the printing press

meant that classical accounts of the mythology of the constellations, together

with other works by classical authors, had become accessible to a wide audience.

Relatively easy access to such source material encouraged the makers of

celestial globes to depart from established tradition, a trend well illustrated

by Vopel's ventures in celestial cartography.

What drove Vopel to add the images

of Antinous and Berenice's Lock of Hair to his globe? The major factor may have

been his use of Trapezuntius's 1528 edition of the Ptolemaic star catalogue, on

page 75 verso of which we find in the last column of the catalogue entries (used

by the editor for additional information and easy reference), the following

names: Aquila, Antinous, Delphinus, Equus prior and Equus

Pegasus— all names of constellations except for Antinous (Fig. 15).

(74)

The inclusion of Antinous among

well-known constellations, suggesting that it is on a par with the others, can

be taken as a straightforward invitation to give Antinous his own image. This

inference is supported by the description in the catalogue proper, which refers

to Informatae circa Aquilam in quibus est Antinous [The unformed stars

around

|

The editor of the 1528 star

catalogue has added a most interesting piece of information in the last column

of the catalogue entry on folio 78 recto that describes the unformed stars Leo

6e–8e which form Berenice's Lock of Hair:

Plocamos

grece latine uero cincinnus hoc est caesaries & coma uirginis Berenices

fortasse crinis qui a poeta callimacho in astra relatus est: Sed cincinnum

barbari tricam uocant.

(75)

[What] in Greek [is called] plokamos

in Latin [is] in fact [indicated by the term] cincinnus (lock of hair),

which refers to the beautiful curl (caesaries) and hair (coma) of

the virgin Berenice, possibly the lock of hair (crinis) that was placed

by the poet Callimachus among the stars. The barbarians, however, call the lock

of hair with the term trica.

Next to the Greek Plocamos (Lock of hair) this text presents a number

of Latin words for hair and lock of hair used by classical authors: cincinnus,

caesaries, coma (of the virgin), and crinis (of Berenice). It

continues by saying that the poet Callimachus told that the Lock of hair was

placed among the stars. The note concludes by remarking that the

‘barbarians’ used trica to name the Lock of hair. This alternative

Latin word for hair was used in the Arabic-Latin translation of Ptolemy's star

catalogue, the translators of which are here referred to as ‘barbarians’,

because in the eyes of the humanists they wrote ‘bad’ Latin. (76)

On Vopel's manuscript globe the unformed stars Leo 6e to 8e are labelled Cincinnis

id est Caesaries & / Coma Virginis. Graece / Πλóκαμος,

indicating that Vopel had already made use of the note in the 1528 edition of

Trapezuntius's star catalogue while preparing his manuscript globe. Why Vopel

then chose the name BERENICES CRINIS for his printed globe is not clear.

It could have been because Crinis was the name used by Hyginus, among other

Roman authors. (77)

The significance of Vopel's espousal of Trapezuntius's star catalogue is

underlined by the publishing enterprises of the humanist Johannes van

Bronckhorst (1494–1570). Van Bronckhorst was born in

He then became professor in mathematics at the university in

The

Many of the textbooks published or

edited in

Other publications by Noviomagus show that his interests were not limited to

the subjects of the trivium. In 1533 he is said to have published a treatise on

the astrolabe and in 1537 an edition of Bede's De temporum ratione. (82)

Also published in 1537 was his

adaptation of Ptolemy's star catalogue. (83)

In 1539 he produced a book on arithmetic, and in 1540 he published a

translation into Latin of the text of Ptolemy's Geography. (84)

Noviomagus's astronomical work of

1537 opens with an introduction on the rudiments of astronomy (his Isagoge).

It is followed by Books VII and VIII.1–3, copied from the printed edition of

1528 of Trapezuntius's translation of Ptolemy's Syntaxis mathematica.

Books VII.5 to VIII.1 deal with the catalogue proper, while the other chapters (VII.1–4

and VIII.2–3) discuss various aspects of the stars. Books VIII.4–6 are

ignored. He ends with some additional notes after chapter VIII.3.

Of special interest is the fact that the longitudes of the stars listed in

Noviomagus's catalogue were adjusted to a later epoch by the addition of a

precession correction of 19° 50′ to the longitudes of the stars,

precisely the amount I established fifteen years ago for Vopel's printed globe

of 1536. (85)

In terms of the Alfonsine trepidation theory then in use, the precession

correction of 19° 50´ holds for an epoch of about 1520, which coincides with

the beginning of the reign of Charles V as Holy Roman emperor. Had a precession

correction been used for an epoch equal to the date of production, about

1536–1537, one could have argued that Noviomagus had calculated this amount

independently, but this does not hold for an epoch of about 1520. (86)

Noviomagus almost certainly

followed Vopel in this respect.

Noviomagus appears to have shared with Vopel an interest in globe

construction, witness his discussion at the end of Book VIII.3 (in which Ptolemy

describes how to construct a precession globe) on the making of a common globe.

Noviomagus refers, for example, to the method of globe-gore construction

described by Henricus Glareanus (1488–1563) in his De Geographia. (87)

Considering that both men worked in

the same college, their common interests seem to imply some sort of related

activity.

Further research is needed to clarify the relationship between the artisan

Vopel and the text editor Noviomagus, but on the face of it their shared

interests would seem to point to an active humanist interest in celestial

mapping in

For Dürer's maps are based on the

Arabic-Latin tradition of the Ptolemaic star catalogue that, in the eyes of the

sixteenth-century humanist, was held to be ‘bad’ Latin. Such maps would

hardly have been considered fitting illustration for a humanist work.

Furthermore, it cannot be said that Vopel produced a humanist celestial globe.

Vopel was not affected by the attitude of those humanists in the liberal

arts who completely rejected, as had the botanist Otto Brunfels (1464–1534),

for example, the adoption of Arabic-Latin text traditions. (89)

Considering the long history of the

Arabic-Latin legacy of star names, it would have been impossible not to borrow

to some extent from the ‘barbarian’, ‘bad’ Latin, tradition. The use of

Greek names for many constellations (eighteen in all) and for some stars (α

Leo, α Vir and α Sco) on Vopel's maps reflects at the same time the

increasing impact of humanist tendencies in nomenclature in celestial

cartography.

Of the various iconographic

novelties on Vopel's printed globe only the images of Antinous, Coma Berenices

and the Kids survived to later centuries. The visual representation of these

asterisms made it easier to identify their specific groups of stars and enhanced

the functionality of a globe unlike, say, the image of a goat eating from a vine

above Boötes that had no association with any stars in the Ptolemaic catalogue.

It is not easy to understand why Vopel added this particular image to his

printed globe and maps. There is no evidence that the goat-eating image appealed

to other sixteenth-century globemakers, and more information is needed before an

explanation can be offered.

The images of Antinous and Coma Berenices were taken over by many

sixteenth-century globe- and map-makers. They were depicted on the celestial

globes of Gerard Mercator (1551), Tilmann Stella (1555), Christian Heiden

(1570), and on the various manuscript globes by Eberhard Baldewein in the third

quarter of the sixteenth century and by Jost Bürgi in the last quarter, and

feature in Johannes Bayer's influential star atlas Uranometria of 1603.

(90)

Mercator re-designed the Lock of Hair, and his authority as a cartographer

ensured the continuing use of the images of Coma Berenices and Antinous on Dutch

globes from 1589 onwards. (91)

Mercator's design for the Lock of

Hair is a useful guide to his influence on later maps and globes.

The maps of Jost Amman (1564) and Jan Januszowki (1585) show Vopel's design

of the Lock of Hair but do not include the figure of Antinous. (92)

In contrast, the copperplate gores of Demongenet (c.1560) depict only

Antinous. Here, though, Antinous is reclining on a low couch, a pose that

recalls the unusual portrayal of Antinous on the now lost ‘Masson cornaline’.

(93)

A similar pose is found on the manuscript globes based on Demongenet's globe

gores. (94)

The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) recorded Antinous as an

independent constellation in his authoritative star catalogue. (95)

This catalogue was the outcome of an ambitious programme Brahe had set up to

‘restore the heavens’, that is, to improve existing knowledge through first

hand observation. To this end, Brahe equipped his Uraniborg observatory, on the

Once completed, Tycho's catalogue

replaced the Ptolemaic one. It was the basis of all celestial cartography

throughout the seventeenth century.

In Prodromus Astronomiae (

The two star groups continued to be displayed regularly on celestial maps

and globes until 1928 when, at the

Antinous was sacrificed and removed

from the celestial scene. Berenice's Lock of Hair, though, was allowed to remain

in modern celestial cartography, testimony to a time when globe- and map-makers

continued to look to the ancients for new data, a trend in astronomy that would

come to an end at the turn of the sixteenth century by the explorations of the

southern sky and Tycho's restoration of the heavens.

I gratefully acknowledge the

invaluable advice in matters of nomenclature offered by Paul Kunitzsch. James

Sykes has generously provided me with material for studying his globe (G4);

Catherine Slowther of Sotheby's kindly provided me with pictures of the G2 globe

gores; Peter Meurer made a number of interesting comments; and Rita Wagner,

Director of the Graphische Sammlung at the Kölnische Stadtmuseum, has allowed

me to use photographs acquired many years ago.

Vedi: https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj05741338 e http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Anonimo%20vopel%201536%20base.htm, nota di Atlascoelestis

Woodcut,

Ø sphere

Above Auriga [lon 75°, lat 60°] is an inscription in a cartouche with the

coat of arms of Cologne on top and two lions at the sides: CASPAR. VO/PEL.

MEDEBACH / HANC. COSMOGRA: / faciebat sphæram. / Coloniæ. A°. 1536. South

of the tail of Cetus [lon 345°, lat −60°]

is an empty cartouche consisting of a rectangular field with decorations around

it. (100)

Cartography: Language: Latin.

Coordinates: circles of latitude every 30° (gore edges). The ecliptic is

graduated [twelve times 0°–30°; numbered every 10°, division 1°]. The

boundaries of the zodiac are indicated by two parallels north and south to the

ecliptic. The symbols of the zodiacal signs are marked north of the zodiacal

constellations. The equator is graduated [0°–360°, numbered every 10°,

division 1°] and labelled: AEQVATOR. The tropics are drawn and labelled:

TROPICVS CANCRI and TROPICVS

Astronomical notes: All 48

Ptolemaic constellations are drawn and labelled: VRSA MINOR, VRSA MAIOR,

DRACO, CEPHEVS, BOOTES, CORONA, HERCVLES, LYRA, CYGNVS, CASSIEPEIA, PERSEVS,

ERICHTHONIVS, SERPENTARIVS, SERPENS, TELVM, AQVILA, DELPHINVS, EQVICVLVS,

PEGASVS, ANDROMEDA, DELTOTON, ARIES, TAVRVS, GEMINI, CANCER, LEO, VIRGO, LIBRA,

SCORPIVS, SAGITTARIVS, CAPRICORNVS, AQVARIVS, PISCES, CETVS, ORION, ERIDANVS,

LEPVS, CANIS MAIOR, PROCYON, ARGO NAVIS, HYDRA, CRATER, CORVVS, CENTAVRVS, FERA,

ARA, CORONA AVSTR, NOTIVS PISOIS [sic]. In addition there are labels

for a number of star groups: PLAVSTRVM (UMa), C. MEDVS(AE) (Per), Hædi

(Aur), Vergiliæ (Tau), Succulæ (Tau), Præsepe (Cnc), Asini

(Cnc), Vrna (Aqr), NODVS (Psc); and for the Milky Way: GALAXIAS.

Also the groups of unformed stars belonging to

The stars are presented by six different marks to indicate their brightness

or magnitude. There is a table in front of Ursa Maior, labelled Stella(rum)

magnitudines, with magnitudes from 1 to 6. The stars are numbered, following

the order of their description in the Ptolemaic star catalogue. Two extra,

non-Ptolemaic stars, in Taurus, numbered 34 and 35, seem to belong to the

Pleiades. There are planetary symbols for astrological associations and many

stars are labelled: Abrachaleus (β Gem), Aldebaran (α

Tau), Alderámín (α Cep), Algomeÿsa (α CMi), Algorab

(γ Crv), Alhabor (α CMa), Alhaior (α Aur), Alkayr

(α Aql), Alkor / Equitator (near ζ UMa), Alphard (α

Hya), Alpherath (α And), Alpheta (α CrB), Alrukaba

(α UMi), Anhelar (α Gem), ARCTVRVS / Azimech aramer (α

Boo), Bata kaÿtos (ζ Cet), Benenatz (η UMa), CANOPVS

(α Car), Deneb adigege (α Cyg), Denebeleced (β

Leo), Dubhe (α UMa), Fomahant (α PsA), Markab (α

Peg), Mirach (β And), Præuindemiatrix (ϵ

Vir), Propus (η Gem), Rass aben (γ Dra), Rass alangue

(α Oph), Rass algethi (α Her), Rigel (β Ori), Riss

alioth (ϵ

UMa), SPICA / Azimech (α Vir), Vuega (α Lyr).

Iconographic features: The style

follows that of Dürer but with a number of variations: a cart pulled by horses

in the body and tail of Ursa Maior; the Kids in Auriga; six tiny female heads

illustrating the Pleiades in Taurus; the two Asses in Cancer illustrating the

Asini; and Lyra as a bird with a stringed instrument horizontally over its body.

Boötes has a lance, a sickle and hunting dogs, and a goat is eating the leaves

of a vine above his head. One of the Gemini has a lyre or a similar instrument

with bow, and there are images of Antinous and Coma Berenices, comprising the

unformed stars belonging to

Nota: vedi http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Anonimo%20vopel%201536%20base.htm, nota di Atlascoelestis

Copper engraved, Ø sphere

Above Auriga [lon 75°, lat 60°] is an inscription in a cartouche with a

coat of arms on top and two lions at the sides: SPHAERA / ASTRONOMICA / aeri

exarata, sicut / eam olim exhibuit Cas/par Vopelius Cosmogr. South of the

tail of Cetus [lon 345°, lat −60°]

is an empty cartouche consisting of a rectangular field with decorations around

it.

Cartography: The same as Vopel 1536

(G1).

Astronomical notes: Almost the same

as Vopel 1536 (G1), but the name of the constellation

Iconographic features: Almost the same as Vopel 1536 (G1). The Pleiades in Taurus are illustrated by four instead of six tiny female heads.

Copper engraved, Ø sphere

Above Auriga [lon 75°, lat 60°] is an empty cartouche with a coat of arms

on top and two lions at the sides. South of the tail of Cetus [lon 345°, lat −60°]

is another empty cartouche, consisting of a rectangular field with decorations

around it.

Cartography: The same as Vopel 1536

(G1).

Astronomical notes: Almost the same

as that of Vopel 1536 (G1). The title of the magnitude table in front of Ursa

Maior is missing. Five constellation names are missing (Cygnus, Cassiopeia,

Delphinus, Navis, Hydra), and five constellation names have a variant spelling: CAEPHE(VS),

LIRA, ERIOTONIVS, CANIS MINOR, NOTIVS PISCIS. The image of Antinous is drawn

but not labelled. Only three subgroups are labelled: C. MEDVSAE (Per), VERGILIE

(Tau) and VRNA (Aqr). Many stars are missing and only one star name is

engraved: MARKAB (α Peg).

Iconographic features: Almost the same as Vopel 1536 (G1). The Kids in Auriga are absent, and the Pleiades in Taurus are illustrated by five instead of six tiny female heads.

Nota 101 e 102 (a cura di Atlascoelestis)

101. Sotheby's, Catalogue

Natural History, Travel, Atlases and Maps (

102. Van der Krogt, ‘The globe-gores in the Nicolai-Collection’ (see note 101), 112–13, no. 20.

Woodcut,

Ø sphere

There is an empty cartouche south of the tail of Cetus [lon 345°, lat −60°]

consisting of a rectangular field with decorations around it.

Cartography: Almost the same as

Vopel 1536 (G1). The tropics are labelled TROPICVS CANCRI and TROPICVS

CAPRICOR[NVS]. The polar circles are labelled CIRCVLVS ARCTICVS

and CIRCVLVS ANTARCTICVS. Around the South Pole are two incomplete labels:

one for the winter solstitial colure: SOLSTITIO and another for the

vernal equinoctial colure: COLVRVS. Outside the constellations most

circles are covered by paint.

Astronomical notes: Almost the same

as that of Vopel 1536 (G1). The title of the magnitude table in front of Ursa

Maior is missing (but it might be covered by paint). Missing are two

constellation names (Ursa Minor and Cancer) and the name of the Hyades in Taurus.

Only five stars are labelled: ARCTVRVS (α Boo), SPICA (α

Vir), CANOPVS (α Car), HIRCVS (α Aur) and ACARNAR

(θ Eri).

Iconographic features: Almost the

same as Vopel 1536 (G1), but here one finds in addition the image of a young man

representing Phaeton at the end of Eridanus.

M1.

A

PAIR OF CELESTIAL MAPS included on the world map by Jeronimo de Girava (

Vedi: http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Girava%201556.htm, nota di Atlascoelestis

1)

Northern hemisphere in the left lower corner of the world map.

A)

Cartography: Polar stereographic projection: from the north ecliptic pole to

south of the ecliptic to include the zodiacal constellations. Coordinates:

circles of latitude every 30°. The ecliptic is graduated [twelve times 0°–30°;

not numbered, division 3°]. The part of equator north of the ecliptic is drawn.

The north polar circle, the Tropic of Cancer and the equinoctial colures are

drawn but not labelled.

B)

Astronomical notes: All northern and zodiacal Ptolemaic constellations are drawn.

There are no labels.

C)

Iconographic features: The style follows that of Dürer but with some

differences: Lyra is a headless bird (note that the orientation of the string

instrument differs from that on Vopel's globe by being placed vertically over

the body, as on Dürer's map); Boötes is presented with lance, club and hunting

dogs; one of the Gemini has a lyre or similar instrument without bow. In

addition there are images of Antinous and Coma Berenices comprising the unformed

stars belonging to

2)

Southern hemisphere in the right lower corner of the world map.

A)

Cartography: Polar stereographic projection: from the south ecliptic pole to the

ecliptic. Coordinates: circles of latitude every 30°. The ecliptic is graduated

[twelve times 0°–30°; not numbered, division 3°]. The part of equator south

of the ecliptic is drawn. The south polar circle, the Tropic of Capricorn and

the colures are drawn but not labelled.

B)

Astronomical notes: All southern Ptolemaic constellations are drawn. There are

no labels.

C)

Iconographic features: A cloud of smoke rises from Ara and a swimming maiden is

at the end of Eridanus.

1)

Northern hemisphere in the lower left corner of the world map entitled: IMAGINES

CELI SEPTEN / TRIONALES CVM DVODECIM / IMAGINIBVS ZODIACI. Outside the map

are two figures. One, labelled PTOLOME / VS / AEGYP / TIVS, wears a top

hat and holds a pair of dividers with a celestial globe in his left hand. The

other figure, labelled AZOPHI / ARABVS, wears a turban and holds a

celestial globe in both hands.

A)

Cartography: Polar stereographic projection from the north ecliptic pole to

south of the ecliptic to include the zodiacal constellations. Language: Latin

and Greek. Coordinates: circles of latitude every 30°. The ecliptic is

graduated [twelve times 0°–30°; numbered every 5°, division 1°]. The names

and symbols of the zodiacal signs are absent. The part of equator north of the

ecliptic is drawn. It is not graduated and not labelled. The north

equatorial pole is labelled Polus mundi Arcticus. The north polar circle

is drawn and labelled: Circ Arcticus. The Tropic of Cancer is drawn and

labelled: Tropicus Cancri. The equinoctial colures (not labelled) are

drawn from the vernal to the autumnal equinox passing through the north

equatorial pole. The solstitial colures (labelled Colurus Solsticiorum)

coincide with the circle of latitude passing through the north ecliptic and

equatorial pole.

B)

Astronomical notes: All northern and zodiacal Ptolemaic constellations are drawn,

and all but one (Draco) are labelled: VRSA MIN / Greek name; VRSA MAIOR /

Helice; CEPHEVS; BOOTES / Greek name; CORONA; HERCVLES / Greek name; LYRA,

AVIS / Greek name; CASSIOPEIA; PERSEVS; ERICHTHONIVS / Auriga; OPHIVCH /

serpentarius; ANGVIS; TELVM; AQVILA; DELPHINVS; EQVICVLVS; PEGASVS; ANDROMEDA;

DELTOTON; ARIES / Greek name; TAVRVS / Greek name; GEMINI; CANCER

/ Greek name; LEO; VIRGO / Greek name; LIBRA / Greek name; SCORPIO

/ Greek name; SAGITARIVS / Greek name; CAPRICORNVS / Greek

name; AQVARIVS / Greek name; PISCES / Greek name. Also the groups

of unformed stars belonging to

C)

The stars are presented by six different marks to indicate their brightness or

magnitude. Outside the map, below Sagittarius, is a table labelled Stellarum

magnitudines, with magnitudes from 1–6, and alongside these the number of

stars within each magnitude class [15, 45, 208, 474, 217, 49]. The stars of the

Pleiades are missing. There are planetary symbols for astrological associations,

and many stars are labelled: Abrachaleus / Herculis (β

Gem), Aldebaran (α

Tau), Alhaior (α

Aur), Alioth (ϵ

UMa), Alkair (α

Aql), Alkor/ Equitator (near ζ

UMa), Alrucuba (α

UMi), Anhelar / Apolinis (α

Gem), Arcturus / Azimech aramer / Alramech (α Boo), Benenatz (η UMa), Capra (α Aur), Deneb algedi (δ Cap), Denebeneced (β Leo), Dubhe (α UMa), Fomahant (α PsA), Makab (α Peg), Mirach (β And), Propus (η Gem), Rass Alangue (α Oph), Regulus / Cabalezet / Greek name (α

Leo), Rasdagel (β

Per), Scheat (δ

Aqr), SPICA / Azimech / Greek name (α

Vir), Stella polaris (α

UMi), Vindemiator (ϵ

Vir), Greek name for Antares (α

Sco).

D)

Iconographic features: The style follows that of Dürer but with some

differences: Lyra is a headless bird (note that the orientation of the string

instrument differs from that on Vopel's globe by being being placed vertically

over the body, as on Dürer's map); Boötes is presented with lance, sickle and

hunting dogs, and a goat is eating leaves from a vine above his head; one of the

Gemini has a lyre or similar instrument without bow. In addition there are

images of Antinous and Coma Berenices comprising the unformed stars belonging to

2)

Southern hemisphere in the lower right corner of the world map entitled: IMAGINES

CELLI / MERIDIONALIS. Outside the map are two figures. One, labelled M.

MANILIVS / OMANVS [sic], wears a headband and holds a celestial globe in his

left hand. The other, labelled ARATVS / CILIX, wears a hood and has a

celestial globe on front of him.

A)

Cartography: Polar stereographic projection: from the south ecliptic pole to the

ecliptic. Language: Latin and Greek. Coordinates: circles of latitude every 30°.

The ecliptic is graduated [twelve times 0°–30°; numbered every 5°, division

1°]. The south ecliptic pole is labelled: Polus Zodiaci. The part of

equator south of the ecliptic is drawn. It is labelled: PARS CIRC AEQVINOC

but it is not graduated. The south equatorial pole is labelled: POLVS mundi

antarct. The south polar circle is drawn and labelled: CIRC. ANTARCTI.

The Tropic of Capricorn is drawn and labelled: TROPICVS CAPRICOR. The

equinoctial colures, labelled COLVRVS AEQVINOCTIORVM, are drawn from the

autumnal to the vernal equinox passing through the south equatorial pole. The

solstitial colures, labelled COLVRVS SOLSTICIORVM, coincide with the

circle of latitude passing through the south ecliptic and equatorial pole. Below

the title is a nonlinear latitude scale, labelled: REGVLA LATITVDINVM

STELLARVM [0°–90°; numbered every 10°, division 1°].

B)

Astronomical notes: All southern Ptolemaic constellations are drawn and labelled:

CETVS / Balena Pristis Leo marinus, ORION, ERIDANVS, LEPVS / Greek name, CANIS

MAIO, CANIS MI. / Greek name, ARGO, HYDRA, CRATER, CORVVS, CENTAV. /

Phyllirides Chiron, FERA / Greek name, ARA/ Greek name,

C)

The stars are presented by six different marks to indicate their brightness or

magnitude. There are planetary symbols for astrological associations, and many

stars are labelled: Acarnar (θ

Eri), Aldebaran / Greek name spelled Λαμπαδιας

(α Tau), Algomeysa

(α CMi), Algorab

(γ Crv), Alphard

(α Hya), Angetenar

(τ Eri), Bata

Kaitos (ζ Cet),

Bedelgeuze (α

Ori), CANOP (α

Car), Deneb algedi (δ

Cap), Deneb Kaytos (β

Cet), Fomahant (α

PsA), Menkar (α

Cet), Rigel / Algebar (β

Ori), the Greek name for Antares (α

Sco).

D) Iconographic features: The style follows Dürer but with two deviations: a cloud of smoke rises from Ara and a swimming maiden is at the end of Eridanus.

M3.

A

PAIR OF CELESTIAL MAPS included on the world map by Matteo Pagano (

2) in

Cosmographia Universalis et Exactissima iuxta postremam neotericorum traditio[n]em. A Iacobo Castaldio nonnullisque aliis huius disciplinæ peritissimis nunc [pr]imum revisa ac infinitis fere in locis correcta et locupletata.

Author: Giacomo di Gastaldi

Contributor: Paolo

Forlani;

Matteo Pagano

Subjects: World - -- Maps and charts -- 1561

Publication Details: [Venice?] : [Matteo Pagano], [ca. 1561]

Language: Latin

Description: Contents: A woodcut map of the world on an elliptical projection; marginal decoration includes portraits of Ptolemy and Strabo, and the celestial and terrestrial hemispheres. On the sheet covering the North Atlantic is a depiction of Philip II of Spain in which the initials 'P.F.D.' are cut, which may be identifiable as those of Paolo Forlani, an engraver in Venice in the 1560s.

Identifier: System number: 005015603

Notes: The date of the map

is assumed from the publication by Matteo Pagano of a booklet by Gastaldi, “La

Universale Descrittione del Mondo” (1561), in which a similar world map is

described.

The seven cartouches are left blank.

Physical Description: 1 map on 9 sheets ; sheets 45 x 40 cm.

Holdings Notes: Cartographic Items Maps R.17.a.9. [A photocopy]

Shelfmark(s): Cartographic

Items Maps C.18.n.1.

Cartographic Items Maps R.17.a.9.

UIN: BLL01005015603

1)

Northern hemisphere in the upper left corner of the world map.

A)

Cartography: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). The north equatorial pole

is labelled Polus mundi Arturus [sic] and the north polar circle Circ

Articus [sic] .

B)

Astronomical notes: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). There is no

magnitude table, and the text on

C)

Iconographic features: The same as Valvassore 1558 (M2).

2)

Southern hemisphere in the upper right corner of the world map.

A)

Cartography: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). There is no latitude

scale.

B)

Astronomical notes: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). The Greek name of

Lepus and the label Balena Pristis Leo marinus for Cetus are left out.

Two constellations have a variant spelling: CANIS MAIOR and HIDRA.

The name of one subgroup is missing (Nodvs coelestis), and one is spelled

differently: Scorpii stelle (Sco). One star name has a variant spelling: Denecb

Kaytos (β Cet).

C)

Iconographic features: The same as Valvassore 1558 (M2).

M4.

A

PAIR OF CELESTIAL MAPS included on the world map by Bernaard van den Putte (

V

https://archive.org/stream/nachrichtenvond07klasgoog#page/n25/mode/2up

1)

Northern hemisphere in the lower left corner of the world map entitled: IMAGINES

CELI SEPTEN / TRIONALES CVM DVODECIM / IMAGINIBVS ZODIAC. Outside the map

are two figures. One, labelled PTOLOMA[EVS] / AEGYPTIVS, wears a top hat

and has a pair of dividers with a celestial globe. The other, labelled AZOPHI

/ ARABVS, wears a turban and holds a celestial globe in his hands.

A)

Cartography: The same as Valvassore 1558 (M2).

B)

Astronomical notes: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). There is a Greek

name for Gemini, but the Greek name for Taurus is missing. Variant spellings of

constellation names: DECTOTON, SAGITTA. There are two additional names

for subgroups: Hædi (Aur) and Vergiliæ. The four Ptolemaic

Pleiades stars and two extra, non-Ptolemaic stars are also marked. Variant (correct)

spellings of star names: Markab (α

Peg); Denebeleced (β

Leo). The area below the name SPICA (α

Vir) is damaged.

C)

Iconographic features: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). Lyra is now a

bird with a head (note that the orientation of the string instrument deviates

from that on Vopel's globe by being drawn vertically along its body as on Dürer's

map).

2)

Southern hemisphere in the lower right corner of the world map, entitled: IMAGINES

CELI / MERIDIONALES. Outside the map are two figures. One, labelled M.

MANILIVS / ROMANVS, wears a headband and holds a celestial globe in his left

hand. The other, labelled ARATVS / CILIX, wears a hood and has a

celestial globe on front of him.

A)

Cartography: The same as Valvassore 1558 (M2).

B)

Astronomical notes: Almost the same as Valvassore 1558 (M2). There is a variant

spelling for Navis: ARCO, and two additional star names: Bellatrix

(γ Ori) and Alhabor

(α CMa).

C)

Iconographic features: The same as Valvassore 1558 (M2).

M5. A

PAIR OF CELESTIAL MAPS by an anonymous maker. Woodcut, 28.5 ×

vedi

http://www.atlascoelestis.com/Anon%20gall%20500.htm

1)

Northern hemisphere

A)

Cartography: Polar stereographic projection: from the north ecliptic pole to

south of the ecliptic to include the zodiacal constellations. Language: Latin.

Coordinates: circles of latitude every 30°. The ecliptic is graduated [twelve

times 0°–30°; not numbered, division 10°, subdivision 1°], and the symbols

of the zodiacal signs are marked. The part of equator north of the ecliptic is

drawn. It is graduated [not numbered, division 10°, subdivision 1°] and

labelled AEQVINOCTIALIS. The north polar circle and the Tropic of Cancer

are labelled respectively: Circulus Acrticus and TROPICVS CANCRI.

The colures are not labelled. The north equatorial pole is labelled but

difficult to read.

B)

Astronomical notes: All northern and zodiacal Ptolemaic constellations are drawn,

and all but one (Serpens) are labelled: Vrsa minor, Vrsa maior, Draco,

Cepheus, Bootes, Corona, Hercules, Lyra, Cygnus, Cassiopeia, Perseus,

Erichthonius, Ophiuchus, Sagitta, Aquila, Delphin, Equiculus, Pegasus,

Andromeda, Deltoton, Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius,

Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius, Pisces. Also the groups of unformed

stars belonging to

C)

Iconographic features: Lyra is represented by a bird with a head (note that the

orientation of the string instrument differs from that on Vopel's globe by being

being placed vertically over the body, as on Dürer's map), Boötes holds a

lance in his right hand, and the Gemini have no attributes. In addition there

are images of Antinous and Coma Berenices comprising the unformed stars

belonging to

2)

Southern hemisphere

A) Cartography: Polar stereographic projection: from the south ecliptic pole to the ecliptic. Language: Latin. Coordinates: circles of latitude every 30°. The ecliptic is graduated [twelve times 0°–30°; numbered every 10°, division 1°]. The symbols of the zodiacal signs are marked. The part of equator south of the ecliptic is drawn. It is graduated [not numbered, division 10°, subdivision 1°]. The south polar circle and the Tropic of Capricorn are labelled respectively: Circulus Antarcticus. and TROPICVS CAPRICORNI. The colures and the south ecliptic pole are not labelled. The south equatorial pole is labelled but difficult to read. There is no latitude scale.

B)

Astronomical notes: All southern Ptolemaic constellations are drawn and labelled:

Cetus, Orion, Eridanus, Lepus, Sirius, Canis minor, Argo navis, Hidra,

Crater, Corvus, Centaurus, Fera, Ara,

C)

Iconographic features: The same as Valvassore 1558 (M2).

1. Herbert Koch, Aus der

Geschichte der Familie Vopelius: familiengeschichtliche Blätter herausgegeben

von Bernhard Vopelius,

2. At the

3. Ernst Zinner, Deutsche und

niederländische astronomische Instrumente des 11–-18. Jahrhunderts (1st

ed., 1956; 2nd enlarged ed., 1967; reprint of 2nd ed.,

4. Robert W. Karrow, Mapmakers

of the Sixteenth Century and Their Maps: Bio-bibliographies of the Cartographers

of Abraham Ortelius, 1570 (Chicago, Speculum Orbis Press, 1993), 558–67.

5. Paul Kunitzsch, Der Almagest.

Die Syntaxis Mathematica des Claudius Ptolemäus in arabisch-lateinischer Überlieferung

(Wiesbaden, Otto Harrossowitz, 1974), 167–68, has a table listing each

constellation with the Greek name, the modern Latin name and the conventional

abbreviations. For a concordance between the two ways of identifying stars, see

Paul Kunitzsch, Claudius Ptolemäus: Der Sternkatalog des Almagest. Die

arabisch-mittelalterliche Tradition. Vol. III: Gesamtkonkordanz der

Sternkoordinaten (Wiesbaden, Otto Harrossowitz, 1991), 187–94.

6. Leonard Korth, ‘Die Kölner

Globen des Kaspar Vopelius von Medebach (1511–1561)’, Zeitschrift für

vaterländische Geschichte und Alterthumskunde 42 (1884): 169–78.

7. Korth, ‘Die Kölner Globen’